| Slavery is a Woman The Art History Archive - Issues

Slavery is a Woman:

Hanging on one wall of the Musée du Louvre, in the company of the gargantuan machines by Jacques-Louis David, Eugène Delacroix, Théodore Géricault, and others, is an exquisitely crafted and modestly sized painting of a black woman. She is shown seated, half-draped, with her right breast bared to the viewer. She sports an intricately wrapped and crisply laundered headdress that appears similar in fabric to the garment she gathers closely against her body just below her breasts. She stares out at the viewer with an enigmatic expression. Although there are no background details that indicate precisely where the sitter is placed, certain details of her physical surroundings—namely, the ancien régime chair and luxurious cloth that drapes both it and her—suggest that she is in a well-to-do domestic space. Portrait d'une négresse (fig. 1) was painted in 1800 by Marie-Guilhelmine Benoist (born Marie-Guillemine Leroulx-Delaville) (1768-1826), a woman of aristocratic lineage who belonged to a small elite circle of professional women painters that included, among others, Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744-1818), Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755-1842), Marguerite Gérard (1771-1837), Angélique Mongez (1775-1855), and Adélaide Labille-Guiard (1749-1803).1 As had been the case with most women artists working at the time, Benoist fit the middle and upper class ideal of "womanhood" in her conforming to the social expectations of women to marry, raise children, and forego a career."2 Although we do not know whether or to what extent Benoist partook in the volatile debates on slavery and gender current during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in France, her painting may be seen as a voice of protest, however small, in the discourse over human bondage. With the portrait, the artist responded to early nineteenth-century French racialism and the less-than-desirable treatment of women by playing upon the popular analogy of women and slaves. The portrait is interesting not just in its aesthetic presentation and historical context, but in its potential for new critical readings. In the following pages, I want to consider Benoist's portrait as a work far more nuanced and layered in signification around race, gender, and class issues than previous assessments of the work have led us to believe.3 I would like to present a reading of the painting based upon a consideration of its racialized and gendered subject matter and style, as well as the gender and social class status of the artist, the historical circumstance surrounding the work's creation, and the multi-directional dynamics of "race" and visuality communicated through the portrait. To this end, my approach will deviate at times from standard modes of art-historical inquiry and venture into a critical evaluation of the painting as a constructed image of "race" and gender. Before doing so, however, certain biographical and historical bits of information must be revealed that inform my unconventional interpretation of the painting. Circumstances The acknowledgement and delineation of historical circumstances have always been critical for contextualizing treatments of race and gender in art. The Portrait d'une négresse was painted in 1800—after the emancipation decree of 1794 in which slaves in the French colonies were (temporarily) liberated and slavery was abolished, but before the reinstatement of colonial slavery by Napoléon Bonaparte in 1802. So the period in which Benoist's portrait was fashioned was one in which the heroicized black image enjoyed considerable popularity in France.4 It has been suggested that Benoist might have executed the work as a tribute to the 1794 emancipation, combining it with the rise of a short-lived feminist movement in France, thereby effectively linking the issues of slavery and the condition of women.5 Of course, all hopes for black and female emancipation were dashed with the reinstitution of slavery in 1802 and with the appearance of the Code Napoléon in 1804, the latter of which imposed harsh social and legal restrictions on women and the former on black immigration into France.6 Benoist's concerns with the status of women and their link to colonial blacks evolved as a result of developments that impacted her life, a life that reads like a suspense novel. She was born into an established family of government administrators and politicians from Brittany. Her father, René Leroulx-Delaville, entered the government administration around 1764. In 1782, he was named director of Louis XVI's saltworks and was subsequently assigned to another government post. He took on several important positions including, in 1792, appointment as a minister in Louis XVI's cabinet. Toward the end of his life, he was named French consul in Rotterdam, where he died in 1798. His brother, Joseph Leroulx-Delaville, was a member of the Assembly of Notables, Deputy of the Orient to the Estates General, and a member of the Constituent Assembly. Benoist's husband, Pierre-Vincent Benoist (1758-1834), a lawyer and avowed monarchist from Angers, also came from an illustrious background. He was a member of the Constituent Assembly and fostered close royalist connections.7 Benoist's marriage to Pierre-Vincent in 1793 further deepened her royalist ties and eventually forced her to become entangled, reluctantly, in the Revolution's politics during its most radical phase in 1793-1794.8 Her close friendships with known monarchists and their sympathizers eventually proved potentially dangerous to her safety, so much so that in 1794 she and her husband were forced into hiding.9 It has been suggested that the Portrait d'une négresse was not commissioned but was painted on the artist's own initiative, and was modeled after a black slave brought back to France by Benoist's brother-in-law, a civil servant and ship's purser who had returned from the French island of Guadeloupe in 1800.10 Africans and colonial blacks were frequently brought to Europe to work in upper class and middle class households and often appear in paintings "as part of a complex ritual of display of . . . the ostentatious wealth the bourgeoisie (and upper classes) accumulated through African slave labor on Caribbean plantations."11 During the time in which Benoist's portrait was painted, planters were allowed to bring slaves onto the French mainland where, legally, slavery had been forbidden since the Middle Ages. French law dictated that once transported onto continental French soil, a slave's status had to be legally changed to that of servant or attendant and registered with the French authorities.12 In all likelihood, therefore, Benoist's sitter was a slave-turned-servant who had no say in the way her body was presented. The artist, always eager to publicize her painting skills, enthusiastically began the task of putting on canvas the "belle couleur noire brillante" that she found by contrasting dark flesh and white cloth. Portrait d'une négresse is an anomaly in Benoist's oeuvre. Prior to 1800, the artist produced mostly portraits and genre scenes in pastels.13 She exhibited sentimental, moralizing portrayals of women, children, and family life which were, generally speaking, expected of women artists by the male-dominated art apparatus during the period and which were very popular with the middle class. Of all the works she exhibited between 1799 and 1804, most of which are lost to us now, Portrait d'une négresse was most highly praised by the Salon critics.14 The painting is unusual in that it deviates from standard representations of blacks in European art which typically show them as colorful additions to a portrait or a scene in which a white master or mistress is the intended primary focus. Most scholars agree that Benoist's portrait was not a study for a larger project as is the case with most eighteenth-century works in which a sole black appears.

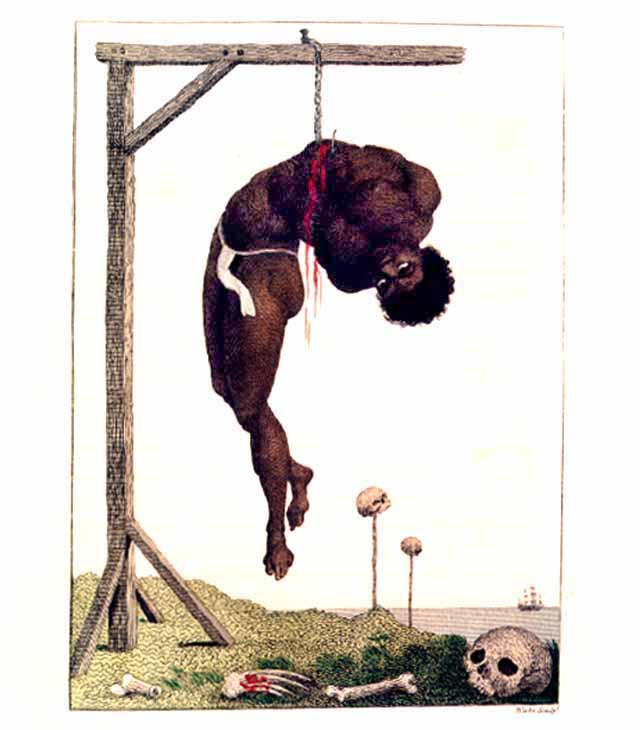

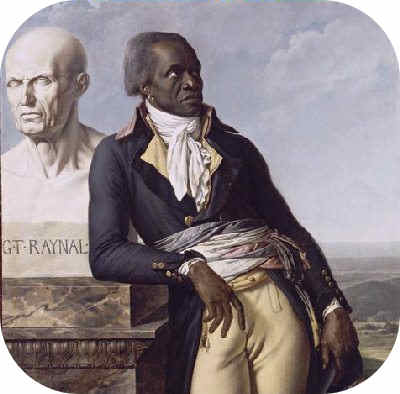

A contemporary art historian, Griselda Pollock, has noted that in Western art black women typically represent "a space in the text of a masculinist modernist culture in which flourishes an Orientalizing, Africanist fantasy that circulates between artists, their models, and contemporary art historians in the twentieth century."16 Benoist's image is intriguing in that it disrupts our perception of portraiture as a genre and should be read as a powerful demonstration of stylistic virtuosity used not only to construct racial otherness in the historical moment, but to relate that process to the assumed un-raced white and, in this case, female rather than male, self. In the process, black woman remains a nameless "negress" despite her individualized physiognomy. She mystifies rather than clarifies the expected function of the portrait genre as a marker of a sitter's identity, social class standing, and occupation. Indeed, Portrait d'une négresse is less a portrait of a black woman and more a portrait of Benoist herself. And in this respect, it is a typical colonialist picture in that the artist who created it made use of the racialized Other to define and empower the colonizing Self. That is, the portrait constitutes a visual record of white woman's construction and affirmation of self through the racial and cultural Other. Benoist's portrait is not only self-reflexive, but is dialogic in that it documents a desire by the artist to command both the aesthetic and the racial in the defining moment of the modern self. The image underscores the observation that national and cultural identities of artists who speak through and for the Other oftentimes "mark themselves and their objects of othering in specific terms of racial, gender, and class differences."17 The portrait goes far to highlight the co-existence of "processes of identification and objectification, [of] mirroring and distancing."18 In the Portrait d'une négresse the harsh reality of the enslaved condition of this particular black woman (and by extension, all black women) is concealed beneath a veneer of aestheticizing and classicizing. However, for all its aesthetic allure and charm, the portrait robs the black sitter of her identity, her voice, and her agency in order to make a statement about the social position and power (albeit limited in the sense of male-dominated politics of the day) of bourgeois and upper class white women at the beginning of the nineteenth century in France. Benoist's portrait gives credence to the observation that "those rendered Other are sacrificed to idealization [exoticism], excluded from the being of personhood, from social benefits, and from political (self) representation."19 This process is underscored by the title Benoist gave to the portrait. Although the image depicts a specific individual, the artist has referred to her only as a négresse—the feminine counterpart of the generic racial designation nègre (Negro).20 Benoist's prerogative not to name is not simply a result of the black woman's race, for three years prior to the portrait, in 1797, the history painter Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1767-1824) produced a striking portrait of a black man called Portrait du Citoyen Belley, ex-représentant des colonies (fig. 4).21 In the historical and art-historical literature, the portraits by Girodet and Benoist are often mentioned and illustrated in relation to one another and are recognized as rare images in that they showcase a single black figure as main focus of a work of art.22 They differ, however, in several respects. Unlike Benoist, Girodet depicts a named individual whose biography and physical presence relate directly to the postrevolutionary moment in which it was painted.23 Belley's dignified yet defiant demeanor speaks directly to the historical circumstances of slavery, abolition, and the tumultuous relationship between the races in the French colonies. Although the exact relationship between Girodet and Belley remains a mystery, it is probable that Girodet's purpose was to visually construct a personage who embodies the democratic ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity brought forth by the French Revolution and should be extended, in principle, to blacks. Portrait du Citoyen Belley is, according to historian Helen Weston, a combined allegorical and straightforward portrait containing elements of idealization and historical "truth."24 Likewise, Benoist's portrait taps into didactic strains of allegory while addressing historical truths regarding slavery and the less-than-desirable condition of women. Whereas Belley is clothed in a uniform that identifies his rank and historical significance as diplomatic representative of black political interests in the colonies, Benoist's negress is partially nude and resigned to her assigned role as slave/servant. In contradistinction to Girodet's politically active black model, Benoist's black woman has been denied individuality and agency. She has been "vacated" and then "filled in" by the artist with self-reflexive, opportunistic ideology that speaks to both Benoist's prowess with the paintbrush and her command over not only the black body as object, but also, by extension, over black domestic labor.25 It is the absent and un-raced self outside the picture frame (i.e., Benoist herself as artist), who has freely exercised her power not to name and by doing so imagines and extends "power, control, authority and domination over a stand-in who she attempts to ‘liberate'."26 In using the black female body as a sign of emancipation for all women, Benoist employs an operative series of struggles rendered in binary terms between feminine and masculine, between emotionalized aestheticism, passive domesticity and the desire for political expediency through portraiture as public action; between enslavement and liberty, black and white, stereotype and sympathy. In other words, I see in this portrait the "classic" ambiguity, struggle, and neurotic exchange of power played out between colonizer and colonized—a state of affairs that has become an all-too-expected feature of racial and cultural relations in the modern Western world.

|

|

|

Portrait d'une négresse as Racial Enterprise With the expansion of slavery in the late eighteenth century, and the simultaneous development, based on a new "scientific" classification of human biological traits, of a hierarchy of races, did the word race acquire its meaning.27 In the case of Benoist's image, racial difference is determined by outward signs on the body—namely, skin color, hair texture, and the shape of facial features such as eyes, nose, and lips. The most prominent racial sign is that of a dark skin pigmentation set off against a blank background and white fabric. Paintings such as Benoist's support the belief that the black subject is powerless before the "fact" of race, even though race was and remains a culturally constructed fiction in which "‘Blackness' is a structure of racist inscription, not a color."28 From the late eighteenth century until the end of the nineteenth century, "race" in French thought was defined and redefined in relation to those social, political, and ideological processes that were coterminous with French social, cultural, and political development. In late-eighteenth-century France, racial thinking as well as racist utterances in print and images, became increasingly normalized and naturalized. In this context, Benoist's portrait was no different from works by other artists who assumed a relationship between physical difference and cultural and national difference. Although Benoist's specific views on black people are unknown, there is little doubt that she believed in a hierarchy of classes and the races, as did everyone of the period regardless of their political persuasion. Nineteenth-century critical responses to Benoist's painting were varied, but reveal much about the then-prevalent attitudes towards race and gender. One reviewer, the staunch royalist Jean-Baptiste Boutard, attacked the painting and its creator by admonishing: "Whom can one trust in life after such horror! It is a white and pretty hand which has created this blackness (noirceur)."29 Along these same disparaging lines, another critic, Charles Thévenin, referred to the subject of Benoist's portrait as "a sublime blurred tache (stain),"30 referencing the black woman as an unclean object, a blot devoid of noteworthy human presence. Both Boutard and Thévenin attacked Benoist based on their belief that the artist had violated contemporary notions of aesthetic propriety. Their judgments were informed by commonly held racist beliefs of their time that blacks were ugly, less than human, and unworthy as the primary subject of any noble art form.31 As was the case with most artists and critics of the period, Boutard and Thévenin viewed blacks as biologically different and set apart culturally and intellectually from Frenchness and whiteness. They saw only the "celebrated beauty of the white hand of the artist in comparison with the diabolic hand of the model."32 For such critics, as well as for some lay observers, the negative shock of blackness—the tache as visible sign and symbol of ugliness and horror—was set in contrastive association with the virtuous attributes of white female purity and beauty. Clearly, Benoist's portrait not only provoked the question of what subjects were worthy of representation but, more specifically, what subjects were appropriate for white women artists of high social standing to engage. The biological determinist notion of race and racial distinction emerged in French representation as part of the development of France's entry into the institutional and psychological structures of the modern world. As David Theo Goldberg has noted, definitions of race and gender along with their attendant representational forms, emerge, develop, and change within the institution of modernity.33 I am defining modernity here in its Foucauldian sense as a discourse of cultural, political, and institutional control and subjugation that is coterminous with the emergence of Eurocentrism and European domination through imperial conquest and rule. In fact, the concept of race is one of the central inventions of the modern world, a point that makes it all the more remarkable that most past and contemporary histories of early nineteenth-century French art avoid altogether the issue of race. Perhaps this is so as not to spoil the central place of French art in traditional accounts of Western modernism and not to destabilize the central position of French revolutionary ideology in modern political discourse. Whatever the reasons, race has always been an ambiguous concept in the annals of modern French history and thought. The concept came about as the result of French involvement in the institution of slavery, abolition, and in the advent of scientific enterprise used to rationalize the enslavement of black Africans. It is difficult to measure, however, the degree to which French perceptions and rationalizations of racial difference within the scientific community impacted points of view about racial difference in the artistic community. Nevertheless, Benoist's portrait demonstrates to what extent gender, race, and class, were significant to the articulation of the artist's subjectivity in the historical moment of French entry into the modern world. With Portrait d'une négresse, we are forced to question race, gender, and class as defining aspects of the collective body politic in the building of French nationhood in which women and blacks were to be included in the abstract ideals of liberté, égalité, and fraternité.34 The portrait underscores the perception that race is a paradoxical component of French entry into the modern world in that "as modernity commits itself progressively to idealized principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity, as it increasingly insists upon the moral irrelevance of race, there is a multiplication of racial identities and the sets of exclusions they prompt and rationalize, enable and sustain. Race is (nominally) irrelevant, but all is race."35 Portrait d'une négresse as Gendered Enterprise Although the Portrait d'une négresse served Benoist as a bold proclamation of the artist's own class standing, gender status, racial/cultural designation, and social aspirations, it is far from a "clear-sightedly objective" exercise.36 The kind and quality of Benoist's engagement with the racial Other was, among other things, determined by gender-specific restrictions on women's activities in art and politics, and based on race and class assumptions about black women at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In an 1806 issue of the conservative paper Journal des débats, Boutard noted of Benoist that she had confined herself to portraiture, which, according to him and his contemporaries, was the genre most suitable for female artists.37 Painting in the eighteenth century was practiced by women exclusively of the privileged class, and was largely viewed as an amateur pursuit. Serious painting, that is to say, history painting, was considered a masculine enterprise reserved for men. The goal of history painting was "to teach, to lead, to instill virtue, and to capture gloire."38 Although, in general, women were indeed pressured into pursuing the so-called lesser genres of still life, floral, animal pieces, domestic genre painting, and portraiture, it has been duly noted that they were not summarily prevented from attempting history painting.39 These genres were considered as more feminized because their only function was to give pleasure to the viewer, and the willingness to please easily was considered part of women's weakness.40 Benoist's characteristic subjects—intimate portraits of women and children—are indicative of the role assigned to women artists within the French academic system at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The number of women allowed to enter into the French Academy was limited and the attempt to exclude them altogether was led by the institution's director, the Comte d'Angiviller, who believed that "too many women would dilute the proportion of history painters" and thus threaten not only the academy's manliness, but also damage its historical legacy of fostering French national and cultural superiority in art.41 Even as women insisted on equal entry into the academy, they continued, categorically, to be denied access to the life classes necessary to produce history paintings. With few exceptions, they were generally denied government patronage and were forbidden from competing for the coveted Prix de Rome. In short, at the time Portrait d'une négresse was produced, painting for women was considered as a "pursuit of gentility, not genius."42 Benoist's first works, exhibited at the annual Exposition de la Jeunesse, from 1784 through 1788, were mostly pastel portraits employing the soft rococo modelling technique favored by her mentor, Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-Lebrun. Vigée-Lebrun, who saw herself as an important role model for Benoist, was confident that the latter's career would be as bright as her own.43 In 1786, Benoist was one of three female students accepted for art instruction into the studio of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) while Vigée-Lebrun's studio was being renovated. Benoist's admittance was made possible by both Vigée-Lebrun's recommendation and by her family's close political and administrative ties with the government. That is, she was able to receive as much instruction as she did because of the social status of the male members of her family, and as little as she did because of her gender. For Benoist and many others, David was the godlike figurehead of sober, serious neoclassical values in art. He was also a staunch supporter of the artistic training of women and encouraged his female students to attempt the study and practice of history painting.44 Although David took in women for art instruction, he assured the academy's administration that the sexes would be strictly segregated and that the women he took in would be refused access to the male nude.45 It was while in David's studio that Benoist adopted his severe, moralizing neoclassical style, clearly revealed in her Innocence Between Virtue and Vice and the Farewell of Psyche, both exhibited in the Salon of 1791 at David's encouragement. In that same year, David urged Benoist to also exhibit in the Exposition de la Jeunesse her history painting titled Clarissa Harlowe at the Archers. The main protagonists of all these works were women. Due to family and social pressures, however, by 1795 Benoist had ceased painting classical subjects and devoted herself to the "feminine pursuits" of portraiture and sentimental genre scenes. Notwithstanding Vigée-Lebrun's strong mentoring, Benoist's single year in David's studio was the most influential on her work. From 1791, her paintings incorporated stylistic traits associated with neoclassicism such as simplified backgrounds, a minimal use of props and clothing, a sculptural approach to modeling the figure, direct lighting, stronger coloration and tonal contrasts. There is no doubt that for Portrait d'une négresse, Benoist was greatly influenced by David in terms of both style and composition. It has been observed that Benoist's portrait is in fact "a negative image of the pale Mme. Trudaine" depicted by David sometime in the late eighteenth century.46 The works are similar in terms of minimal background detail, seated position, facial expression, and gathered hands around the abdomen.47 Portrait d'une négresse constitutes the most publicly recognized example of Benoist's continued foray into the masculinist enterprise of neoclassicism. In Portrait d'une négresse, the black body is put forth as a "foreign element" within an upper class cultural and domestic space. The image is built upon notions of the female body as vulnerable, nurturing, part of the cult of domesticity and interiority. However, this space of "feminization" and interiority, created for the most part by the juxtaposition of skin and cloth, is presented to us in the "masculinized" visual language of neoclassicism. The gendered nature of the painting's style has been underscored by the comments of several past and contemporary observers. Male critics of the period asserted condescendingly that Benoist's brand of neoclassicism was laced with the "feminine" traits of delicacy and sensuality assigned to the rococo and to its practitioners. Even the choice of words used by one contemporary female observer to characterize the portrait speaks to the continued "problem" of gender in the work's production. The work, she notes, combines "the graceful fluidity and coloristic harmonies learned from Vigée-Lebrun with the three dimensional modelling and firm contour taught . . . by David."48 Believing at the time in the prerogative and superiority of men and masculinity in all creative endeavors, many past male observers doubted the authenticity of Portrait d'une négresse and were convinced that David himself had painted it or "at least directly assisted in [its] execution."49 Joseph-Etienne Esménard noted of Benoist's portrait that "its finish and purity of drawing" brought to mind the school of David.50 In his 1801 Lettre sur la situation des Beaux-Arts en France, the Swedish critic Bruun Neergaard noted, "Madame Leroulx-Delaville has given us the Portrait d'une négresse. It is easy to see, from the purity of the drawing, that she is a student of David."51 These and other observers judged Benoist's portrait strictly in relation to David's stylistic influence and neglected to see Benoist's contribution in terms of the work's potentially radical subject matter. By viewing Benoist's portrait only in terms of Davidian neoclassicism and the gendering of style, I believe these critics affirmed and praised the masculinist aspect of the painting while silencing or disavowing the work's potentially subversive feminist appeal. Interestingly, whereas gender difference has been uniformly constituted in neoclassicism's masculine valence, racial distinction has not. As a heroic style indicative of high culture and the founding of democratic nationhood, neoclassicism must necessarily bar racial difference from its semiotic systems of operation. In this respect, Benoist's portrait is unique in its exploitation of racial difference expressed within the visual language of neoclassicism. The portrait is also unusual in the sense that, among other things, a black female subject rendered in the neoclassical style is used to voice the more "authentic" masculine traits of morality and virtue. Because the characteristics of virtue, rationalism, and virile masculinity were major components of neoclassicism and the classical culture it promoted, the style itself is often associated with masculinity and is typically set in opposition to the "feminine" rococo style that preceded it.52 In addition, many professional women artists were perceived by male observers and by other women at the time as taking on "male" attributes in presenting themselves as independent professional artists.53 For example, commenting on Benoist's temporary move to David's studio and the influence it had on her and other women artists, one male observer noted that "the merit of women and their valiant participation in the arts is one of the distinctive features of these times . . . Benoist [and Angélique Mongez] have no fear of entering as initiates into the more virile [my italics] practices of David's studio."54 Another observer stated of Benoist that "it was necessary [for her] to be manly to be able to stand the discipline of David's teaching" and her Portrait d'une négresse was "painted with a wholly masculine discipline and does not possess any of the feminine graces."55 By engaging in a masculinist mode of artistic production through a "virile" style, and by alluding to volatile subjects that demanded public action—slavery and women's rights—Benoist's Portrait d'une négresse becomes an inherently political and gendered painting. I contend that it was the correlation and conflict between masculine and feminine, between emotionalism and heroic action in neoclassical painting that perhaps attracted Benoist to employ the ennobling and classicizing language of the style to a black woman. In other words, in her Portrait d'une négresse, Benoist attempted to exploit for political expediency the stylistic and gendered dualisms within neoclassicism—male versus female, hard versus soft, stoicism versus emotionalism, master/mistress versus slave/servant. Benoist's portrait negotiates between public and private, male and female, familiar and anonymous, erotic and intellectual, via an image that conveys political and social import through its gendered and racial aspects. Benoist challenged the restrictions on women artists of her day by linking the "feminine" genre of an intimate portrait with politically charged subject matter (slavery and abolition), the intellectual consideration and visualization of which were emblematically reserved for men.56 Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the slavery and abolition debate remained at the core of determining and designating who was and who was not a member of the French nation. Feminisms Although one might argue that there was no single coherent feminist agenda in 1800, nor is it necessarily the case that every painting of a woman by a woman is about women's rights, I want to consider Benoist's portrait as both a work of consensus-building and "feminist" protest. Until 1789, the push for women's rights had been spearheaded by a few female and male agitators. During the Revolution, a minority of women, especially in Paris, became politically visible and vocal. A new kind of feminism developed after 1789 which was characterized by less rhetoric and more action, especially among its working class supporters.57 Previously voiced vague statements advocating equality evolved into specific demands by women for educational, economic, and legal and political rights. But by 1800, pro-slavery and reactionary political forces recovered ground lost in the Revolution. It is quite possible that Benoist's portrait may have been a reaction against the Jacobin outlawing of the women's clubs and its revocation of the right of speech for women in public meetings. Undoubtedly, Benoist must have sympathized with the frustration, anger, and fear of many female political activists whose activities were curtailed with the Reign of Terror and who witnessed the execution of several women of disparate political tendencies—from Marie Antoinette to Olympe de Gouges. In its thematic strategies, Benoist's portrait closely relates to early nineteenth-century feminism and the writings of women authors such as Olympe de Gouges, Germaine de Staël, and Claire de Duras. As was the case with the literary works of these women, Benoist's portrait visualizes, through a black presence, the themes and issues of concern about, namely, class distinction among women, women's status as the "slaves" of men in patriarchal society, and women's abilities to act subversively within that societal structure. The works of all three writers stressed, in varying degrees and intensities, differences of race (African and European), gender (male and female), and social class (slave/servant and bourgeois).58 Prior to Napoleon's elimination of women's rights and curtailment of abolition, one of the crucial events in the development of a feminist movement in France had actually occurred in England with the 1792 publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797).59 This tract was published to popular acclaim throughout Europe. It appeared one year after a similar but less well-known tract on the topic of women, Déclaration des droits de la femme (Declaration of the Rights of Woman), by Olympe de Gouges. Both works championed women's political rights and education, and linked women's struggles directly to colonial slavery.60 As well, both de Gouges and Wollstonecraft did not hesitate to use the term slave (esclave) when discussing the social position of women in society. Wollstonecraft wrote her book to counter Jean-Jacques Rousseau's ideas on the separate educational needs of women and the cultivation of their "natural" female sensibilities. In her quest for sexual egalitarianism, however, Wollstonecraft conceded the inevitability of male superiority and admitted "a woman's weakness" in trying to argue that when women were free, they would be in a "better" position to serve their husbands.61 Although less so with the works of Wollstonecraft, most scholars make a ready association in the writings of Olympe de Gouges between feminism, abolitionist propaganda and "strategies of self-fashioning" that take into account self-awareness of her limitations as a woman writer and the methods she employed to circumvent patriarchal dominance in the literary domain.62 Although de Gouges and Wollstonecraft were important figures in the early French feminist movement, they were not the dominant voices on the subject of women's rights; that role was held by men. Several major eighteenth-century philosophes, including Montesquieu, Voltaire, Rousseau, Brissot de Warville, Condorcet, and Diderot, had something to say on the subject of women's rights in conjunction with the issue of slavery. Rhetorical engagement—be it verbal or visual— in debates around slavery and abolition, particularly after the successful slave uprisings on Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1791 and before the reinstitution of slavery in the French colonies in 1802, would have been deemed part of revolutionary political discourse and, therefore, reserved primarily for men to engage. With the help of men such as Condorcet, who publicly acknowledged himself as an ami des femmes as well as an ami des noirs, women protested actively for their political and social rights. Condorcet was encouraged by his friend Brissot, founder of the French abolitionist group, the Amis des Noirs, to agitate for the democratic rights of women. In his 1790 essay "Sur l'admission des femmes au droit de cité (On the Admission of Women to Civil Rights), Condorcet spoke out against prejudice and injustice against women and, in the same breath, compared female emancipation to that of black Africans.63 Although ultimately unsuccessful in ameliorating the situation for women and black slaves, both Condorcet and Brissot emphasized the link between the two causes. Other writers, too, specifically related the condition and rights of women to those of slaves. For example, in 1792, the French humanitarian writer Jean-Baptiste Aubert du Bayet called women "the victims of their fathers' despotism and of their husbands' perfidy" and warned that French law could not maintain women in a state of slavery.64 Pierre Guyomar, a philosophe of considerable reputation, linked sexual and racial discrimination in his 1793 Partisan de l'Egalité politique entre les individus: I submit that one half of the individuals in a society have not the right to deprive that other half of its inalienable right to express its own desires. Let us free ourselves at once of the prejudice of sex just as we did of the prejudice against the color of the negro.65 Feminists of the period—both male and female—used arguments of defense that closely paralleled those used by the Amis des Noirs. One such argument was that women were human beings who shared in the natural rights of man. Another was that women, like blacks, once freed could fight for France and contribute socially and economically in the name of patriots. Some of these arguments resulted in an ironic backlash. In order to assert that women were just as patriotic as men, feminists often "conceded in affirming their biological role as childbearers and as the mothers of all citizens."66 I think it is an easy matter to trace the parallels between the politicizing tactics of race and gender used in literary and abolitonist debates and Benoist's Portrait d'une négresse. Some of the "strategies of self-fashioning" employed by Olympe de Gouges appear to reverberate with Benoist's portrait. I conclude this to be the case even though there is no hard evidence to support the claim that Benoist either personally knew Olympe de Gouges or read any of her writings. Notwithstanding, it has been confirmed that in 1789-90, Olympe de Gouges publicly associated herself with the Marquis de Condorcet and the Société des Amis des Noirs.67 For Olympe de Gouges, "black slaves had become less her cause than her muse, compelling her to write . . ."68 Even though de Gouges's dedication and sincerity around the cause of manumission may have been genuine, it has been pointed out that she did not hesitate to use the abolition and feminist debates "to foster a more prominent public identity as a self-styled femme de lettres."69 It is clear to me that Benoist's actions are in line with those of Olympe de Gouges in that she, too, took advantage of the then-popular link between feminist causes and abolitionist propaganda. Like de Gouges, Benoist might have viewed abolitionism and feminism "not as a coherent ideology so much as an available social identity"70 with which one could fashion oneself publicly as a credible professional artist. However, even though Benoist's painting may have challenged stereotypical expectations of women's social and artistic talents, the artist also met certain male expectations regarding roles assigned to women. To make a statement about women's role in society that could elicit a supportive response from a male spectator, Benoist employed neoclassicism, a "masculine" style, and exploited black women, a popular subject matter, with potential appeal to exotic and erotic male fantasies. "Race" and the (Al)lure of Allegory Black woman's transplantation from the colonies into the artist's studio easily allowed for the "negress's" transformation into useful symbolization—from the colonial/imperial to the feminist/erotic. Benoist understood the relation between misogyny at home and the exploitation of colonial slaves abroad. Her subject matter carries serious political and moral implications. Taking into account the artist's indoctrination into the idea of painting as a socializing act for women in her position, Benoist foregrounded a discursive posture in relation to gender and slavery that was simultaneously less and more eroticized in order to appeal to a heterosexual male audience through which her standing as a professional painter was determined. Her portrait provokes an ethnographic and erotically objectifying subtext—the dynamics of which operate under a veil of allegory, classicizing, and aestheticizing. Indeed, an important and pervasive strategy employed in most late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century French illustrations about slavery, abolition, and colonial trade was allegory. Allegory is a part of "semiology which approaches paintings and prints as a system of signs and not perception."71 It is pictorial rhetoric used as a substitute for abstract discourse. Benoist's portrait belongs to this discourse of semiology in that it functions as allegorical symbol and emblem intersecting with such lofty ideas as "Liberty," "Revolution," "Republic," and "France"—ideas that contain and carry their own respective symbols and complex relations. In France, allegorical prints with abolitionist messages were typically incorporated into books as illustrations for colonialist, political, or scientific tracts. These were seen by educated elites and were not distributed to a broad audience.72 Thus, a major drawback to the use of allegory in gauging the practical relevance of a black presence in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in France was that its accessibility was restricted to intellectual circles who, in turn, tended to limit outrage against slavery to cerebral debates about the rights of French (male) citizens alone. Between 1794 and 1802, black men and black women became visual signifiers for philosophical rumination over the abstract ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité, rather than as primary catalysts to direct public action. There is, however, a benefit to allegory in relation to the black presence in general and to Benoist's portrait in particular, for as symbolic or metaphorical narrative, allegory sometimes can and often does operate to contest and disrupt the narrative assumptions of colonialism.

It is difficult to know exactly how erotic the exposed breast would have appeared to Parisian audiences in 1800. Certainly the presence of the bared breast would have been scandalous had it not been intended to be read in allegorical or symbolic terms. Indeed, Benoist had access to several allegorical models of the exposed breast, the most noteworthy being Portrait of Mme. D'Aguesseau (ca. 1770; Bucharest Art Museum, Romania) and Peace Bringing Back Abundance (ca. 1798) (fig. 7), both produced by Benoist's mentor, Vigée-Lebrun. With the latter work, the bared breast, symbolizing the idea of plenty, is read as part of a relatively unproblematic allegory when associated with white women.78 The precise origins of the exposed breast as a symbol of liberty in France are not known, but are probably rooted in the classical myth of the Amazon—a mythology created by men and centered on war, sex, ethnography, politics, and rites of passage.79 An image of the bare-breasted Amazon in classical works of art connoted a reversal of sex roles, for Amazons were participants in the outdoor world, the body politic. They reputedly severed their right breasts to "prevent their interference with hunting, fighting, and javelin throwing."80 Retaining her left breast for breast-feeding, an Amazon was able both to preserve her mark of womanhood and to participate in public action associated with men. Benoist's use of the exposed breast within the historical moment of postrevolutionary feminism and slavery, references the inside/outside, domestic/public, female/male dynamics so rigidly codified within French patriarchal society and neoclassicism—the intermachinations of which Benoist attempted to critique through her Portrait d'une négresse. On yet another level, the exposed breast of Benoist's black sitter serves to reinforce the then-popular association of black slave women's hypersexuality with their origins in hot climates. This relationship was popularized especially in travelogues and in works of contemporary fiction.81 Although it was customary for black women in the colonies to go barebreasted due to the heat, Benoist's portrait is no slice of colonial life. The black woman has been taken out of her native context, removed from familial ties and familiar surroundings. She has been deracinated, dislocated, de- and re-historicized; consciously displayed by a French artist in a Paris studio. Isolated from her original geographical and genealogical contexts, the black woman has come to represent whatever is projected onto her by the artist, her contemporaries, and by present-day viewers. The black figure is denied personhood and becomes only a sign of what Gayatri Spivak has referred to as the "vagueness of the negress' geography"—a constructed entity likened to "la superbe Afrique."82 Her presentation "functions as interpellation . . . [a] calling up of subjects into an essentially bourgeois and collective psychic space."83 Complementing the black woman's bared breast is yet another object of visual allure—that of dark flesh. Art historian Gen Doy has pointed out that the exposed upper body could have been merely Benoist's means of demonstrating her skill at painting flesh—an opportunity that was disallowed to most women artists during the period due to restricted access to the nude.84 Also, we might well keep in mind that Benoist painted the portrait for public display and visual perusal by a primarily all-male public and critical audience. The exposure of so much dark flesh in a manner potentially received as erotic, may have shocked or even horrified some viewers (such as Boutard and Thévenin). Griselda Pollock has put a different spin on the display of flesh within the historical context of slavery and has suggested that Benoist's painting visually references the slave auction block, "where naked men and women were exposed to the calculating gazes of their would-be owners, who checked their teeth, felt their muscles and fondled their genitals to make sure of a good buy."85 This mode of exploitation was "supported by the punitive practices of stripping, beating and otherwise violating black bodies in public as signs of white power and ownership."86 Although Benoist's black woman does not appear to have been physically abused, the psychological damage resulting from her vulnerable situation is, I believe, readable through her facial expression and body language. Pollock also notes that the sitter's hand is placed near her genitals, drawing attention to that area and visually alluding to the Venus Pudica typology in which the gesture to cover the breasts and genitalia have the adverse effect of drawing increased attention to them.87 Notwithstanding such exploitation and psychological violation of the body, it has been suggested that the gathering gesture of the left-hand across the figure's lap might well signal resistance on the black woman's part—guarding against further exposure and full possession by the viewer's gaze. If this is indeed what is happening, then the black woman's gesture of protection may well be the only agency, albeit subtle, she is accorded. In addition to the exposure of breast and flesh as visual indices of meaning, there is another allegorical element in Benoist's painting that needs examination—the headdress and its symbolic references to the Phrygian cap of liberty, the African-style headwrap, and to black women's labor. "Badge of Enslavement," "Helmet of Courage" The black woman's headwrap and partial nudity are signs that mark her as different from white womanhood. As well, they constitute visible markers of white woman's command over black woman's labor. By focusing on the black woman's corporality and by juxtaposing dark skin with white cloth, Benoist has directed attention to black woman's otherness in the realm of the visual, the physical, and the social. Art historian Griselda Pollock has outlined the history and semiotic significance of the headwrap in context of the formulaic appearance of black women in European visualizations of Orientalist and Africanist fantasy. She has described the headwrap as "a highly specific signifier. . . [that is] too powerful a sign of the exotic," having the ability to "Orientalize" a painting; to generate and circulate the "politics of race, colonialism, and sexuality."88 It was with the eighteenth-century slave trade that the headwrap became a familiar sign of servitude and poverty for black women in the European colonies and in the United States.89 Since cloth was produced domestically, most often by black women, the headwrap was also associated with black women's labor. Helen Foster has asserted that "(white) French women knew of the West African headwrap from written descriptions and from pictorial illustrations."90 In fact, Foster uses Benoist's painting as visual evidence that French women "actually saw the headwrap being worn by African women brought to Europe."91 Although its supposed origins in Africa made it representative of African continuity in the New World, the actual origins of the headwrap are unknown. It has been suggested that an Arabic influence is possible and that the headwrap derived from the male turban. If this is true, then the link supports the element of exoticism ascribed to Benoist's image and its potential association with Orientalist representational practices.92 There are many suggestions as to the function of the headwrap. It serves as an imposed mark of one's status as enslaved laborer. It was of practical use to prevent infestation of lice and other scalp diseases. And it was useful in absorbing perspiration during work. In the Caribbean and in the American South, the headwrap took on a function as "a uniform of communal identity " that encoded resistance to one's enslaved condition.93 So, as both a "badge of enslavement" and a "helmet of courage," the headwrap was paradoxical. In the case of Benoist's portrait, the headwrap may operate as an instrument of identity and rebellion, even though its very presence here also serves as a signifier of difference imposed upon the sitter by a privileged white woman whose own sense of identity depended on black woman's labor, physical submission, and forced anonymity.

The headwrap was not, however, the exclusive domain of black women. White women, in particular white artists such as Vigée-Lebrun, often wore headwraps when engaged in the act of painting. With several self-portraits, such as one from 1790 (fig. 8), Vigée-Lebrun often represented herself sporting a headwrap while painting, actively engaging the viewer who becomes a stand-in for the subject being rendered. The headwrap communicates to the viewer that the artist is laboring. The relationship between the headwrap, women's work (specifically, the manufacture and cleaning of cloth), and black servitude are noteworthy aspects of Benoist's portrait. It is important to reiterate that the headgear speaks to the signification of fabric (here, crisply laundered) in the master/servant relationship, between white woman and laboring black servant.94 The black woman's "imprisoned" status within a "bourgeois" domestic space is reinforced by how skin and cloth relate in her physical surroundings—specifically with the ancien régime chair and the luxurious fabric that drapes both it and her. The black woman constitutes an acquired item among luxury goods.

Another relevant tidbit about the Phrygian cap revealed by Korshak that is significant to one possible meaning behind Benoist's portrait is that its origins, also traced back to Greek art, reveal that it was used to represent the people of Phrygia and, by extension, came to stand for anyone from exotic regions. As the cap of "foreigners," the Phrygian cap also "appeared on alien captives and became a recognized symbol of the prisoner."98 This history relates the condition of Benoist's black woman as a servant/slave (i.e., a domestic "prisoner") and exotic to the Phrygian cap and classicizing allegory. Although Korshak neglects to mention it, the Phrygian cap was typically worn by men, not by women. In relationship to the cap's suggestive classical and exotic symbolism in Benoist's painting, the fact that the Phrygian cap became a signifier associated with the enfranchisement of male slaves only, supports my argument that Benoist consciously employed masculinist tropes and symbolic gestures in order to empower and communicate meaning germane to women. The painting's allusion to the Phrygian cap and African headwrap, coupled with the multiple meanings of the exposed breast, the focus on contrastive textures of flesh and cloth, and the painting's neoclassical style—all work together to connect the idea of the liberty of the black colonial slave with the hopeful emancipation of women. So, in painting a portrait of a black woman, Benoist had a host of allegories and historical occurrences from which to draw upon that carry the significance and conceptual impact of her image beyond mere display of aesthetic virtuosity alone. I propose that Benoist made conscientious and pointed use of meaningful allegories and symbolizations in a period when gains from the Revolution that were thought to benefit women and blacks, no matter how seemingly minor, were being eroded. Some contemporary observers might perceive the painting's allusion to the Phrygian cap of liberty, as well as the exposed breast, not as subversive strategy as I have suggested, but as evidence of "displaced cultural manifestations of the exclusion of women from political life."99 The argument that "there was a concerted effort by men to silence, marginalize, and erase women's voices from the public and political domains" has been challenged by Doy who makes insightful arguments about the relationship between women and allegory during the revolutionary era.100 Doy has acknowledged that during and after the Revolution women of all classes were refused legal political rights. However, she also points out that even though the Revolution did deny women these rights, it also "opened up new possibilities for political and economic activity by women which can not be measured simply in terms of legal political rights granted by bourgeois legislation."101 Benoist's portrait is a testament to one possibility for a woman artist to express political concerns during a time when women of all classes were increasingly restricted from participating in direct public action. Portrait d'une négresse was perhaps Benoist's personal protest against the increasingly anti-woman and pro-slavery atmosphere in 1800. It was her best means of repudiating the anti-feminist and racist policies of her day while working within the culturally sanctioned, male-dominated domain of art production. "Race" and Visuality: The Gaze Revisited Benoist's portrait not only addresses the "fact" of French historical participation in slavery and abolition, but it also engages a visuality in which the complications of race, class, and gender get produced, reproduced, and circulated within those historical phenomena. By "visuality," I refer to the ways in which discursive concepts and codes such as race get caught up and circulated within the domain of the visual.102 Benoist's portrait addresses more than just our eyes; it speaks to complex human relationships and desires that engage the artist, the sitter, and the viewer. Within the complicated structure of Western patriarchy and political economies, vision and visuality are multiple—that is, they can be "hetero- and homo-sexualist, gendered, racist, racial, etc."103 Jacqueline Rose has summarized the importance of analyzing race as a significant aspect of visuality: "the introduction of racial politics into visual space, a racial politics which is also a sexual politics, reconfigures the relation of image to identity, of identity to its undoing [and] reconfigures what we might call . . . tradition and desire."104 With Benoist's portrait, we are in familiar territory in that racial and erotic forms of representation are not only embraced, but are disrupted as well. Viewer identities and identifications are engaged and are put into conflict. Portrait d'une négresse challenges static notions of the racial in visuality through its multiple networks of looking. The dynamics of viewing and the erotics of the gaze are played out among three protagonists: the black sitter, the (unseen) white artist, and the contemporary viewer. The tensions produced by these players in multiple gazes are highlighted in the crisscrossing dynamics of seeing, being seen, and not being seen. Benoist's painting is about viewer location and it raises the question of exactly who is looking at whom and how the viewer identifies with the subject viewed. It is a work that engages both history and contemporary viewership in that it speaks to the social, political, and psychosexual nuances of "race," gender, and colonial desire in the act of looking. I want to briefly enter into this web of visual exchange to tease out what I see as complex and multiple positionalities that force an analysis of the portrait from critical perspectives that do not necessarily adhere to a reliance upon empirical readings of history alone. Discourses about the gaze typically concern issues of pleasure and knowledge, power, manipulation, and desire.105 The discursive and dialogic complexity of the image and import of the gaze indicate that one cannot simply read the work as evidence of white-over-black and male-over-female structures of oppression. There are additional complicating networks of looking and power relationships at work here. In most feminist theories of the gaze, the power of the look is erotically inscribed. It is men who supposedly possess the power of the gaze and, as such, women are subjected to it and reduced to objects. Women become, like slaves, commodities or "capitalist objects of [possession and] symbolic exchange . . . in market economy."106 This regime of power is particularly meaningful within the context of colonial slavery and domestic "servitude"—the lived contexts of Benoist's black woman. However, recent scholarship in areas outside art history, in particular cinema and performance studies, has suggested that there are alternate gazes irrespective of gender that reorder the importance of the visual and produce more fluid forms of subjectivity.107 Benoist's portrait allows for such alternate gazings. Viewing the gaze as only phallocentric is problematic in this instance, for as a woman who happened to be a professional painter, Benoist has deployed meaning regarding her own tenuous and ambiguous position vis-à-vis patriarchal power in 1800. With Benoist's portrait, the one-on-one confrontation propels us into a visual and emotional entanglement with the black woman. In this instance, the nature of one of many possible dialogic exchanges occurring between viewer and viewed stresses the play between the optical and the tactile. Both define what is seen as an object and both are underscored by the sensual rendering of smooth flesh set in visual and tactile contrast with fabric. Here is a perfect moment of what Martin Jay has called "ocular desire" or "erotic projection in vision," where "the bodies of the painter and viewer [are] forgotten in the name of an allegedly disincarnated, absolute eye."108 As with Caravaggio's early paintings of seductive male youths, Benoist's black woman stares back at us while radiating, and indeed complicating, an erotic "energy sent our way."109 The implicit erotic address of the black woman in the gaze broaches the seeming necessity of an eroticized exoticism apparent in most colonialist imagery. Robert Young has convincingly argued that the majority of colonial representations are pervaded by images "of transgressive sexuality . . . with persistent fantasies of inter-racial sex."110 In the case of Benoist's portrait, interracial and homoerotic desires are implicit in the exchanged gazes between artist and sitter. This is not to say that Benoist or the sitter was homosexual, but it does force one to consider the ways in which same-sex wants, needs, and desires can be generated and circulated in the interracial colonial gaze. Because of its dialogic charge, the gaze forces us to assume that the relationship between Benoist, the black woman, and the contemporary viewer is one in which there is a struggle occurring in terms of power and hierarchy. The returned gaze of the black woman, in the sense of altering the I-you/self-other relationship, does not work in this case because by looking back, the black woman is unable to dislodge herself from the objectification effects of the gaze sent her way. She is forever othered, forever locked into a "crushing objecthood."111 At the same time, the black woman's look of quiet resignation could be taken as thoughtful, woefully introspective, passive, troubled, even dignified—an uncertain interpretation that further confounds any definitive reading of the painting and secures the possibility of competing senses or strategies within the work. Benoist's portrait forces the one observed (the black woman) into a state of "permanent invisibility," while the state of the observer (Benoist and the assumed white viewer), although not technically present in the painting, is pronounced. This is the opposite of the typical panoptic model that emphasizes the subjective effects of imagined scrutiny and "permanent visibility" on the observed, but fails to explore the subjectivity of the observer.112 So, precisely who is the master/mistress and who is the subordinate is not so clear in this case. Indeed, the historical realities of slavery and colonialism in the year 1800 would have rendered the gaze upon the black woman as clearly subjugating rather than as a gaze of mutual equality. However, Benoist's assumed sympathy toward the black woman and her own oppressed status as a woman vis-à-vis patriarchal culture dislodge any fixed positionality of the gaze. As well, Benoist's image provides a bridge between the all-female space of the home/studio and the mixed gender space of the Salon. Despite the fact that women would have also seen this work at the annual exhibition, it was subject to critical readings (such as those by Boutard) largely determined by a predominantly male community. I think Benoist had this reality of the contemporary moment well in mind when she started the portrait. Hal Foster has acknowledged the menacing aspect of the gaze, referring to it as part of "a politics of sight" where "menace is a social product, determined by power, and not a natural fact."113 The fracturing or destabilizing of the gaze occurs when the looker is in turn looked at—when the viewer becomes spectacle to another's sight. When this happens, as it does in Benoist's portrait, the question of where the subject resides surfaces. All three participants (artist, sitter, and viewer) constitute viewing subjects. Where each resides is constantly shifting. Each is the result of changing locales of subjective and intersubjective formation since multiple identifications and positionings can be associated with the gaze. This is to say that viewing subjects (Benoist and the contemporary viewer), their objects of vision (the black woman), and the dynamics of visual exchange that operate among them, are complexly produced. Conclusion Even though Benoist's painting is aesthetically successful and technically proficient, and although her work constituted an attempt "to locate [herself through] an African woman [as surrogate] in political [and artistic] modernity," the ultimate result was, I believe, a political failure.114 The portrait "reduced" a potentially radical icon of liberty for blacks and women to an aesthetic level of sensualism for male consumption. While attempting to negotiate the scientific and aesthetic codes associated with the depiction of blacks and women, Benoist ended by catering to the status quo desires of men. Her attempt to create a historical and moral style on combined feminine and masculine terms succumbed to the masculinist mode and formal strategies she employed. Benoist's portrait is part of high culture that is positioned against feminism. High culture tends to exclude the knowledge of women artists produced within feminism, and also works in a phallocentric system of signification in which woman, whether white or black, is reduced to a sign within the discourse on masculinity. The ambivalence of agency and identity for both women and blacks has always been a significant part of the equation of modernity. In this respect, both Benoist and her black subject have something in common. It is this struggle that helps chart and define modernity and its ambivalences of agency.115 The lack of agency and the inability of black woman to control the imaging of her own body in the nineteenth century, constitutes a major problem of which we are reminded in Benoist's portrait. The significance of the (re)presentation and reinvention of a black woman by a white woman artist at the very beginning of the nineteenth century in France is intimately and ultimately connected with the workings of patriarchal power in society. In the end, both Benoist and her "negress" were slaves to a male-dominated culture. However, the same portrait also exposes the cold reality of the oppression of blacks and women at the dawn of the nineteenth century in that both sitter and painter represent victims caught in a system fostering subordination and erasure of that system's oppressed members even in the face of their attempts to assert themselves.