| Understanding Islamic Art of the 16th & 17th Centuries The Art History Archive - Arabic Art

THE COLLECTION OF PRINCE SADRUDDIN AGA KHAN

By Shehbaz H. Safrani Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan has one of the finest private collections of Islamic art in the world. The most striking feature of this marvellous collection is the fact that it required a mere thirty years to be put together. Obviously, the Prince is an aesthete and connoisseur of art. However, he is known to have relied upon scholarly advice from the noted Harvard University Islamic art historian, Stuart Cary Welch. Professor Welch who is curator of Islamic Art at Boston's Fogg Museum and New York's Metropolitan Museum, and has long acknowledged Prince Sadruddin's patronage and friendship, is quick to point out that ultimately, the Prince made the final decisions. During the 1950s, while the Prince attended Harvard University, the appreciation of Islamic art had not approached its present level of demand. Discerning dealers in New York offered him fine and often rare examples of Islamic art. Gradually, the Prince acquired from European dealers in Paris and Geneva, where he still maintains a second home. He also bought from London dealers and bid regularly at Sotheby's and Christie's auctions on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Prince's Islamic art collection is comprehensive both in Muslim chronology and geography. He is constantly striving to strengthen his collection and upgrade its quality. Consequently, to concentrate his attention upon Muslim aesthetics, he recently sold his celebrated collection of African art. It would be difficult to summarize the enormous scope of Prince Sadruddin's collection. On the other hand, it is possible to stress the fact that his collection is best represented by the Arab, the Ottoman Turkish, the Safavid and Qajar Persian, the Mughal as well as Indian nineteenth century "Company" painting and manuscripts. Islamic decorative arts, ceramics and the minor arts, many of which can be found in the Prince's collection, will not be dealt with in this article. Among the Arabs, calligraphy is the highest art-form. Muslims are people of the book. The Quran (Koran), the Muslim scripture, is the most revered Islamic text. So much so that even those Muslims who are unable to read Arabic, which is the sole language of the Quran, know a verse or two at least. Some Muslims, equally untutored in Arabic, can recite the entire Quran and know it by heart. The educated Muslims also share a similar interest in the Quran. Royal members of the House of Saud, such as the late King Feisal, knew the Quran, chapter and verse, and could recall any portion of this holy book at will.

Two types of written calligraphy were preferred, Kufic and cursive. Kufic, which originated from the town of Kufa in Iraq, is geometric, with a distinct rigidness. Due to this physical characteristic, Kufic is ideal for chapter headings, as well as wall inscriptions on Muslim mosques and minarets. The cursive script, the more popular of the two, still used in newspapers, is precisely what the term implies, flowing and easily readable. Basically, all other Islamic scripts are variations of the Kufic and cursive, and all of them tend to be highly inventive and frequently seem like a new style. In Muslim architecture and in the Qurans, Muslims invariable used a combination of both the Kufic and the cursive scripts. But the numerous styles derived from the Kufic and cursive are utterly fascinating. Prince Sadruddin possesses many copies of the Quran. Among all of them, he has one Quranic page which is an outstanding example of Islamic calligraphy. It dates from the early tenth century, approximately three hundred years after Prophet Muhammad's death in 632 A.D. As this page is from North Africa it is all the more interesting, for it sheds light upon a region generally considered late in the flowering of Islamic art. The lettering is in gold, written in Kufic style, on a blue vellum, which is extremely rare. It is believed to be one of several folios, now housed in various collections, from a Quran presented to the mosque in Mashhad by Caliph as-Mamum (A.D. 813-837). Incidentally, a number of Qurans have been discovered recently in Yemen, all of them dating to the early years of Islam. Even in retrospect, this stunning sample from Prince Sadruddin's collection is a small but significant indication that the Arabs were diligent when it came to writing the word of Allah. Furthermore, the Prince's Quranic page attests to the fact that Muslims aspired to creating beauty within the confines of calligraphy.

Turkish history spans several centuries. An adventurous people, highly disciplined and efficient administrators, the Turks terrorised and disrupted many people. Then, in the wake of victory, they controlled vast territories that included portions of Central Asia, Western Asia and eventually Egypt. Many of the great empires can be traced to Turkish ethnic origins such as the Mameluks, Timurids and Mughals. All of these people developed and integrated singular styles in art which are best defined by their dynastic names. In 1453, when Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks, another new era in Islamic art emerged. These Ottomans employed the most adept and artistic calligraphers available. They commissioned splendid illuminated Qurans and enhanced the standards of the decorative arabesque. Above all, they developed the book into a single flowing concept. As a result the bindings (of handsomely hand-tooled leather) are as exciting as the pages themselves.

Prince Sadruddin has several examples of Ottoman calligraphies, manuscripts and paintings. Turkish arts thrived under Ottoman patronage. The thrills the Ottomans must have experienced at seeing the art of the Islamic book evolve under their aegis, can still be had from studying them. In fact, the Ottoman sultans acquired works of art for illustrated manuscripts and paintings, from all over the Muslim world - especially from Persia, and cities such as Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo, renowned for their skilled artisans and artists. While the calligraphers were striving to produce their finest art for the sultans, these Ottoman sovereigns, with their prodigious concern for excellence, also turned to architecture. As a result, there are distinct hints of architectural refinements in some of the Ottoman paintings in Prince Sadruddin's collection, including the portrait of Sultan Selim II and a portrait of an Ottoman official. A cursory glance at Muslim paintings will indicate an emphasis on headgear. A huge, tulip-shaped turban, favoured by Ottomans, is one such distinctive headgear among those worn by Muslims. It is a means of recognising the Turkish origin of the wearer. Ottoman paintings reveal the foremost achievements of Muslim portraiture west of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Those intrigued by these works of art would do well to study the Ottomans as they were painted in the West by Venetian painters such as Bellini, and by later masters such as Johann Kopenski. There is more pleasure to be derived once there is an understanding of Islamic art, rather than merely considering it an exotic aspect of world art. There is no doubt that Prince Sadruddin's collection is particularly strong in Persian art, while again, the emphasis is on the art of calligraphy as applied to the Quran. The preference for this geographical area should not be surprising when one learns that Prince Sadruddin's ancestors came from Persia. Despite the change in his family's fortunes and notwithstanding contemporary politics, the Prince is warm-hearted towards Persia. It is Persia that contributed to the renaissance of Islamic art, and indeed, Persia is crucial to any discussion of Muslim cultural heritage.

Before nineteenth century, Perisan Muslim arts are best seen in ceramics. An exception to this is the Seljuk calligraphies (1055-1258), of which Prince Sadruddin owns several eleventh century example. The Seljuks are remembered for their arts, but Persia was transformed after the Mongol conquest in the thirteenth century. Despite this change the Il-Khans, who were descendants of the Mongols, patronised the arts of the book. For all its brief reign, this Il-Khanid age inspired generations of Persian painters. All the same, Persian pictorial art is generally conceived as beginning under the aegis of the Timurids in the fifteenth century. It is in great measure the genesis of Persian painting. Moreover, subsequent painting in Persia and India is ultimately studied from Timurid sources as well, and as far as Islamic painting in Persia is concerned, the cities of Tabriz and Herat enjoyed the same kind of prestige as Florence and Rome in Renaissance Italy. Bihzad, for example, who is generally considered among the greatest Muslim painters, lived in Herat.

|

|

Iran embraced the Shiite sect of Islam at the time of the Safavid dynasty. The Sunni sect, which is larger, claims the majority of Muslims. Whereas theological discussion is not pertinent here, it is wise to remember that Prince Sadruddin, like his forebears, is Shiite. He is the son of Aga Khan III (1877-1957). Prince Karim the present Aga Khan, is Prince Sadruddin's nephew. The followers of the Aga Khan are a celebrated group among all Muslims. They are entrepreneurs with philanthropic interests who believe in the Aga Khan and accept his spiritual leadership. The Aga Khan's followers are based in Bombay, which has long served as their headquarters. Although many live in metropolitan cities such as Bombay, Karachi, Nairobi, Mombasa and Johannesburg, others are scattered around the world. Most of them are prosperous, self-confident and hard-working Muslims. These attributes represent a positive element and should be given greater attention than the lacunae of Islamic theology. In so far as Prince Sadruddin is concerned, until recently he served as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and was nearly elected Secretary General of the United Nations, following the tenure of Kurt Waldheim. Such pragmatic achievements enable us to conceive the picture of a Muslim aesthete who is also a man of action. It is also possible, furthermore, to see Prince Sadruddin in the context of past Muslim patrons of art. The Safavids of Persia are a fine example. Within the first generation, the Safavids (1502-1736) had established themselves as powerful patrons of art, no different from their Medici contemporaries in Renaissance Italy, the Mughals in India and the Ming emperors in China. The Safavids went so far as to accord calligraphers an esteemed position similar to that of painters. Shah Tahmasp (1524-1576), one of the most eminent Safavid patrons of painting, spent two decades in order to attract the best painters to his court. Having done so, he went ahead to inspire a stylistic harmony among his court painters. Such a royal incentive to paint had far-reaching consequences, some of which can be seen in Prince Sadruddin's collection. Generations of Persian painters and patrons considered the "Shahnamah", the Persian epic by the poet Firdausi (933 - ca.1020), as their biggest pictorial challenge. In Persia, the "Shahnamah" held the sort of literary position that Homer's "Odyssey" had among peoples of the northern Mediterranean. Prince Sadruddin has two pages from a "Shahnamah" made for Shah Tahmasp. On one page, attributed to the painter Aqa-Mirak, dated 1532, there is a rendering of the poet Firdausi, "Firdausi Encounters the Court Poets of Ghazna." On the second page, attributed to Muzaffar Ali, painted 1530-1535, is the legendary hero Rustam pursuing Akvan (the demon). Both these pages have been assigned to Tabriz, one of the two great Persian cities noted for its paintings.

However, Shah Tahmasp eventually lost interest in the arts while still in power. Soon, the neglected painters departed for new ateliers in Ottoman Turkey and Mughal India. There, at nearly opposite ends of Safavid Persia, these gifted artists contributed to the increased flowering of Islamic painting. This visual excitement is also garnered from Prince Sadruddin's collection. Meanwhile, Persian patronage acquired a democratic trend in the final years of Shah Tahmasp. Shah Abbas I (1587-1629) and his successors discovered this egalitarian growth in the demand for inexpensive paintings. Besides the Shah and the aristocracy, the new patrons included bourgeois elements as well as career professionals such as soldiers. The physical form of drawings and paintings became a single page rather than an entire manuscript full of illustrations. No doubt some of these single page paintings were meant to be subsequently bound in albums. At that time this popular concept - of the single page painting and drawing - appealed to patrons in India and Turkey as well. Images in these low-priced paintings tended to be introverted. These works of art also departed from the established tradition of anonymity and, on occasion, were signed. Gradually, Western painting influenced Persian art through trade, diplomatic ties, evangelist and maritime contacts. This Europeanised aspect of Persian painting developed a formidable style in the nineteenth century and is celebrated simply as Qajar painting. Among the Qajar dynasty paintings in Prince Sadruddin's collection is a striking portrait of Fath Ali Shah, dated 1819. Prince Sadruddin's great-grand-father, the first Aga Khan, was the son-in-law of Fath Ali Shah. Indian Islamic art is syncretised with Hindu aesthetics. Even a casual glance at the similarities between the Hindus and Muslims of India is sufficient for a start. In religious practices, during festivals and occasions of mourning, including funerals, the two diverse religious groups come together in India.

The "Muharram" is a period of mourning for Ali and his family, including his sons, Hasan and Husain, and their followers. Ali, a cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, was martyred along with his family and followers. The Shiites accept Ali as the successor of the Prophet Muhammad. The Prophet had not nominated his successor. Ali's position had been challenged and he lost. This event, dating to the seventh century A.D. is commemorated with Shiites dressed in black and reciting elegies in front of "alums", the Shiite standards, usually free-standing calligraphy created in silver or copper, and at times even of gold. In the case of Indian Shiites, they carry the "taziya", a green or white paper mosque or mausoleum in miniature. The "taziya" is borne to the water's edge, then released in the water. Similarly, the alums are also immersed in water. While the inexpensive, though religiously inspired taziya is left to float and disintegrate in the water, the alums, expensive and with considerable iconic significance, are returned to their special shrines or stored in religious treasuries until the following year. The rituals of the alums and the taziya are worth studying alongside Hindu customs that prevail during the festival of Ganesha, the son of Siva. Whether Muslims, with these rituals, follow Hindus, or vice versa, is unimportant. The fact that remains striking is the similarity in this case of the two diverse faiths of Indian peoples - Hindus and Muslims. Small wonder that among conservative Muslims outside the subcontinent, the Indian Muslims are treated as country cousins at best.

The early beginnings of Islam in India were limited to the coastal waters of the subcontinent. The Arabs arrived by sea and settled in Sind, now part of Pakistan, and also along the regions north of Bombay and at the tip of southern India. These events took place in the early eighth century A.D. As most of these Arabs traded, India remained undisturbed until the Afghans descended into the plains of Hindustan in the tenth and eleventh centuries. All the same, Islamic art made little impact beyond Delhi, where the Sultanate was established and where some of its architectural remains can still be seen. Late into the thirteenth century the Muslims suddenly seemed to gain control of northern India and by the fourteenth century, their presence was felt as far south as the Deccan plateau. The architecture of the Tughlaq dynasty (1320-1398) and the somewhat later dynastic consolidation of Muslim kingdoms in the Deccan led to wonderful cities being founded such as Bijapur, Bidar and Golconda. Prince Sadruddin has an entire manuscript of a 1399 Quran ascribed to Gwalior. It is a rare and important work of art, quite aside from its religious significance. By the time the Mughals arrived in India in 1526, traces of Islamic presence could still be felt among the Hindu majority. By tradition, Hindus delighted in their scripture, but historiography, travelling accounts and memoirs were second nature to Muslims. Muslims kept journals. Imagine a boy of thirteen, standing inspired, conquering Hindustan, then setting out to landscape gardens. This was Babur (1526-1530), who founded the Mughal Empire (also known as the House of Timur) and continued writing his memoirs and composing poetry. Babur's son, though effete in comparison to the great Mughals, nonetheless played a vital role as an art patron. Humayun (1530 - 1556), Babur's son, exiled to Safavid Persia, brought back to India painters trained in the ateliers of Shah Tahmasp. Thus Humayun, often overlooked, is to be accepted as a catalyst. Once Akbar (1556 - 1605) took charge of the Mughal empire from his father Humayun, he extended it and improved his relations with the chivalric Hindus, the Rajputs. It was then that Muslim art experienced a metamorphosis in India. Emperor Akbar has long epitomised the renaissance man in India. In fact he is credited with the Mughal renaissance. With his government under control, a magnificent court that contained "Naorattan", nine of India's most gifted men in the highest echelons of his empire, Akbar retained the best available painters. These talented artists synthesised the Mughal painting style from Persian, indigenous Indian and European sources. The realistic painting showed the diversity of Indian life, and included some specimens from the plethora of India's fauna and flora. The Akbari paintings concentrated on action.

Akbar's son Jahangir (A.D. 1605-1627), was a half Hindu, the son of Akbar's first wife, the Rajput Princess Joda Bai. Unlike the history painting and illustrations of religious epics under Akbar, both Hindu and Muslim, Jahangir championed individual portraits and natural history subjects. Shah Jahan (1627 -1657) Jahangir's son, turned more towards religion. He lived at a time when the Mughals were at the height of their prosperity, and the paintings of his court depict the formal elegance of Mughal India. A cold, distant, even somewhat restrained effect marked the paintings of an age best remembered for the Taj Mahal (completed in 1654).

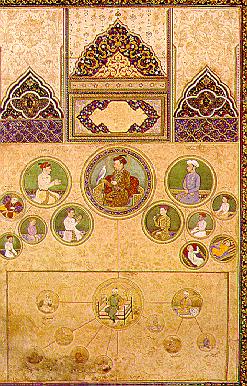

So, from this rich spectrum, Prince Sadruddin has several examples of Mughal paintings, covering all the leading epochs. The early Mughal paintings show the Timurid strains, the Mongol links (obvious in their sinicised eyes) and the rock formations idealised in Chinese paintings. The Safavid elements mingled, the Hindus contributed, and what surfaced as Mughal art is well represented in Prince Sadruddin's collection. The "Pictorial Genealogy of Jahangir" is a painting that to my mind typifies the abiding enthusiasm which Muslim patrons of art have had for Islamic history. This is what I consider the "roots-syndrome" which is indicative of a continuing heritage. Along with anonymous Mughal painters, there are such famous names as Abd al-Samad, Makund, Basawan, Mitra, Balchand, Abu'l-Hasan, Bishnadas, Muhammad'Ali; they are all represented in the Prince's Collection. This is not a "Who's - Who" of Mughal painters but a sophisticated round-up of historical scenes, courtiers, gorgeous tulips and aged pilgrims - a synthesis, one might say, of the best Mughal paintings that have become available in the last thirty years. There are fine examples from the schools of Deccani painting. The 1650 "Floral Fantasy" is typical of the excellence for which the Prince aspired, when putting all these diverse Islamic works of art together. Then there are the paintings from the twilight years of the Mughals and the British Raj, such as Story-teller, Dancer and Musicians, dated 1810 - 1820 from the Fraser Album that Sotheby's auctioned a few years ago. The setting is full of men eager to enjoy themselves, entertain and be entertained, simply by making music and there is an unmistakable air of revelry. The oral tradition of narration, so deeply ingrained in the Muslim psyche, is evoked in this painting. This was a world governed by poetry and enhanced by dancing. It is this quality and the amazing diversity of all types of flowers from the vast fields of Islamic art, that one detects in the collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. The beauty of it all is the fact that the Prince is continuing to collect Islamic art. A very small portion of it has been on view at New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art. A wider selection entitled "Arts of the Islamic Book," an exhibition curated by Anthony Welch and Stuart Cary Welch ( the two scholars are unrelated) originated at the Asia Society in Manhattan in the autumn of 1982. From there it travelled to the Kimbell Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, and the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, during 1983. List of Works:

| |