Chinese Landscape Painting

The Art History Archive - Chinese Art

This Website is Best Viewed Using Firefox

Mountain Water

By Charles Moffat - July 2008.

Many critics consider landscape to be the highest form of Chinese painting. The time from the Five Dynasties period to the Northern Song period (907-1127) is known as the "Great age of Chinese landscape". In the north, artists such as Jing Hao, Fan Kuan, and Guo Xi painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to suggest rough stone. In the south, Dong Yuan, Ju Ran, and other artists painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork. These two kinds of scenes and techniques became the classical styles of Chinese landscape painting.

Beginning in the Tang Dynasty, many paintings were landscapes, often shanshui ("mountain water") paintings. In these landscapes, monochromatic and sparse (a style that is collectively called shuimohua), the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature (realism) but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature.

By the late Tang dynasty, landscape painting had evolved into an independent genre that embodied the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature. Such images might also convey specific social, philosophical, or political convictions. As the Tang dynasty disintegrated, the concept of withdrawal into the natural world became a major thematic focus of poets and painters. Faced with the failure of the human order, learned men sought permanence within the natural world, retreating into the mountains to find a sanctuary from the chaos of dynastic collapse.

In the Song Dynasty period (960-1279), landscapes of more subtle expression appeared; immeasurable distances were conveyed through the use of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. Emphasis was placed on the spiritual qualities of the painting and on the ability of the artist to reveal the inner harmony of man and nature, as perceived according to Taoist and Buddhist concepts. One of the most famous artists of the period was Zhang Zeduan, painter of Along the River During the Qingming Festival.

During the early Song dynasty, visions of the natural hierarchy became metaphors for the well-regulated state. At the same time, images of the private retreat proliferated among a new class of scholar-officials. These men extolled the virtues of self-cultivation—often in response to political setbacks or career disappointments—and asserted their identity as literati through poetry, calligraphy, and a new style of painting that employed calligraphic brushwork for self-expressive ends. The monochrome images of old trees, bamboo, rocks, and retirement retreats created by these scholar-artists became emblems of their character and spirit.

Under the Mongol Yuan dynasty, when many educated Chinese were barred from government service, the model of the Song literati retreat evolved into a full-blown alternative culture as this disenfranchised elite transformed their estates into sites for literary gatherings and other cultural pursuits. These gatherings were frequently commemorated in paintings that, rather than presenting a realistic depiction of an actual place, conveyed the shared cultural ideals of a reclusive world through a symbolic shorthand in which a villa might be represented by a humble thatched hut. Because a man's studio or garden could be viewed as an extension of himself, paintings of such places often served to express the values of their owner.

The Yuan dynasty also witnessed the burgeoning of a second kind of cultivated landscape, the "mind landscape," which embodied both learned references to the styles of earlier masters and, through calligraphic brushwork, the inner spirit of the artist. Going beyond representation, scholar-artists imbued their paintings with personal feelings. By evoking select antique styles, they could also identify themselves with the values associated with the old masters. Painting was no longer about the description of the visible world; it became a means of conveying the inner landscape of the artist's heart and mind.

During the Ming dynasty, when native Chinese rule was restored, court artists produced conservative images that revived the Song metaphor for the state as a well-ordered imperial garden, while literati painters pursued self-expressive goals through the stylistic language of Yuan scholar-artists. Shen Zhou (1427–1509), the patriarch of the Wu school of painting centered in the cosmopolitan city of Suzhou, and his preeminent follower Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) exemplified Ming literati ideals. Both men chose to reside at home rather than follow official careers, devoting themselves to self-cultivation through a lifetime spent reinterpreting the styles of Yuan scholar-painters.

Morally charged images of reclusion remained a potent political symbol during the early years of the Manchu Qing dynasty, a period in which many Ming loyalists lived in self-enforced retirement. Often lacking access to important collections of old masters, loyalist artists drew inspiration from the natural beauty of the local scenery.

Images of nature have remained a potent source of inspiration for artists down to the present day. While the Chinese landscape has been transformed by millennia of human occupation, Chinese artistic expression has also been deeply imprinted with images of the natural world. Viewing Chinese landscape paintings, it is clear that Chinese depictions of nature are seldom mere representations of the external world. Rather, they are expressions of the mind and heart of the individual artists—cultivated landscapes that embody the culture and cultivation of their masters.

Guo Xi

(Chinese, c. 1000–1090)

Guo Xi was the preeminent landscape painter of the late eleventh century. Although he continued the Li Cheng (919–967) idiom of "crab-claw" trees and "devil-face" rocks, Guo Xi's innovative brushwork and use of ink are rich, almost extravagant, in contrast to the earlier master's severe, spare style.

Old Trees, Level Distance compares closely in brushwork and forms to Early Spring, Guo Xi's masterpiece dated 1072 (National Palace Museum, Taipei). In both paintings, landscape forms simultaneously emerge from and recede into a dense moisture-laden atmosphere: rocks and distant mountains are suggested by outlines, texture strokes, and ink washes that run into one another to create an impression of wet blurry surfaces. Guo Xi describes his technique in his painting treatise Linquan gaozhi (Lofty Ambitions in Forests and Streams): "After the outlines are made clear by dark ink strokes, use ink wash mixed with blue to retrace these outlines repeatedly so that, even if the ink outlines are clear, they appear always as if they had just come out of the mist and dew."

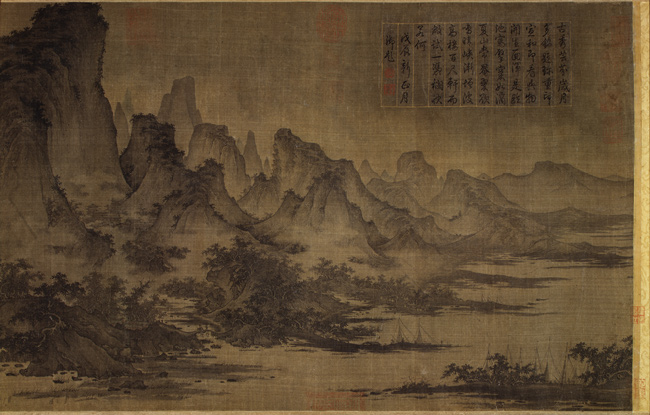

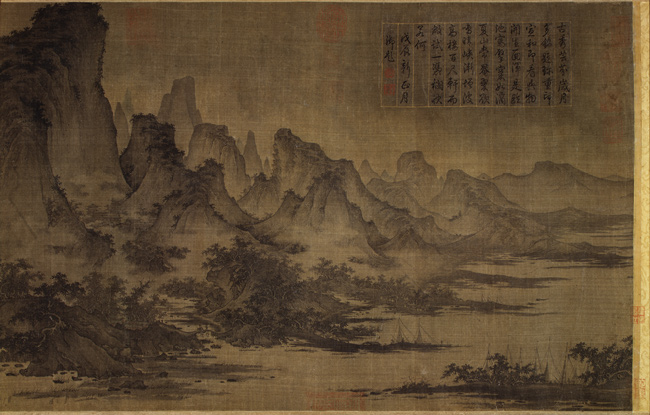

Qu Ding

(Chinese, active c. 1023–1056)

Between 900 and 1100, Chinese painters created landscapes that "depicted the vastness and multiplicity" of creation itself. Viewers of these works are meant to identify with a human figure in the painting, allowing them to "walk through, ramble, or dwell" in the landscape. In this landscape, lush forests suffused with mist identify the time as a midsummer evening. Moving from right to left, travelers make their way toward a temple retreat, where vacationers are seated together enjoying the view. Above the temple roofs the central mountain sits majestically, the climax to man's universe.

The advanced use of texture strokes and ink wash suggest that Summer Mountains, formerly attributed to Yan Wengui (active c. 970–1030), is by a master working in the Yan idiom around 1050, a date corroborated by the presence of collectors' seals belonging to the Song emperor Huizong (r. 1101–25). Although there is no record of any painting by Yan Wengui in Huizong's collection, three works entitled Summer Scenery by Yan's eleventh-century follower Qu Ding are listed in the emperor's painting catalogue.

Ma Yuan

(Chinese, active c. 1190–1225)

Ma Yuan, a fourth-generation member of a family of painters, was a leading artist at the Southern Song painting academy in Hangzhou. A city of unsurpassed beauty, Hangzhou was graced with pavilions, gardens, and scenic vistas.

In this album leaf, which shows a gentleman in a gardenlike setting, the jagged rhythms of the pine tree and garden contrast with the quiet mood of the scholar, who gazes pensively into the bubbling rapids of the cascade.

Zhao Mengfu

(Chinese, 1254–1322)

Zhao Mengfu, a leading calligrapher of his time, set the course of scholar-painting by firmly establishing its two basic tenets: renewal through the study of ancient models and the application of calligraphic principles to painting. In Twin Pines, Level Distance the landscape idiom of the Northern Song masters Li Cheng and Guo Xi has become a calligraphic style. Rather than simply describe nature as it appears to be, Zhao sought to capture its quintessential rhythms. The characteristics of rocks and trees, felt by the artist and acted out through his calligraphic brushwork, are imbued with a heightened sense of life energy that goes beyond mere representation.

In a long colophon on the far left of the scroll, the artist expresses his views on painting: "Besides studying calligraphy, I have since my youth dabbled in painting. Landscape I have always found difficult. This is because ancient [landscape] masterpieces of the Tang, such as the works of Wang Wei, the great and small Li [Sixun and Li Zhaodao] and Zheng Qian, no longer survive. As for the Five Dynasties masters Jing Hao, Guan Tong, Dong Yuan, and Fan Kuan, all of whom succeeded one another, their brushwork is totally different from that of the more recent painters. What I paint may not rank with the work of the ancient masters, but compared to recent paintings I daresay mine are quite different."

Wang Meng

(Chinese, c. 1308–1385)

Wang Meng depicted scholars in their retreats, creating imaginary portraits that capture not the physical likeness of a person or place but rather an interior world of shared associations and ideals. He presents the master of The Simple Retreat as a gentleman recluse. Seated at the front gate of a rustic hermitage, he is shown holding a magic fungus, as a servant and two deer approach from the woods. In the courtyard, another servant offers a sprig of herbs to a crane. The auspicious Daoist imagery of fungus, crane, and deer as well as the archaic simplicity of the figures and dwelling evoke a dreamlike vision of paradise.

In creating this visionary world, Wang transformed the monumental landscape imagery of the tenth-century master Dong Yuan. Rocks and trees, animated with fluttering texture strokes, dots, color washes, and daubs of bright mineral pigment, pulse with a calligraphic energy barely contained within the traditional landscape structure. Encircled by this energized mountainscape, the retreat becomes a reservoir of calm at the vortex of a world whose dynamic configurations embody nature's creative potential but may also suggest the ever-shifting terrain of political power.

|

See Also

Dong Qichang

Gong Xian

Hua Yan

Huang Gongwang

Huang Tingjian

Giuseppe Castiglione

Ni Zan

|

Wen Zhengming

(Chinese, 1470–1559)

The Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician (Zhuozheng Yuan) was established on the site of an ancient temple in Suzhou by the censor Wan Xianchen (active c. 1500–1535) during the Jiajing reign (1522–66). In 1527, after an unhappy stay in Beijing, Wen Zhengming returned to Suzhou, where he was given a studio in the garden. In an album dated 1535, Wen depicted thirty-one views of the site, each accompanied by a poem and a descriptive note. Sixteen years later, at the age of eighty-one, the artist painted this second album representing eight views. The garden still exists in Suzhou today, but centuries of renovation make it difficult to identify the scenes that Wen painted.

In these works, Wen achieved the ideal integration of the three separate arts of poetry, calligraphy, and painting ("the three perfections"). With characteristic restraint, he chose to use only ink in the paintings, but, aided by the poems, the quiet and exquisite images easily transport us to that magical, autumnal moment in the garden.

Kuncan

(Chinese, 1612–1673)

Born on the Buddha's birthday, Kuncan took Buddhist monastic vows at the age of twenty-six and became an ardent follower of Chan (Zen) Buddhism. After the establishment of the Qing dynasty, he lived in Nanjing, where his circle of friends included a number of poet-painters who considered themselves loyal yimin ("leftover subjects") of the vanquished Ming dynasty. In 1659, he visited Mount Huang, the scenic "Yellow Mountain" in southern Anhui Province, and, inspired by the beauty of the site, decided to devote himself entirely to painting. For Kuncan, painting was a path to the self, and he brought to his art the importance of selfhood espoused by later Chan practitioners.

Kuncan's landscapes, painted in the densely textured style of the Yuan master Wang Meng (ca. 1308–1385), are often accompanied by inscriptions that describe a physical, as well as spiritual, journey through mountains and over waters. In Wooded Mountains at Dusk, the artist depicted himself as a wandering pilgrim seated beneath a natural rock bridge:

I want to go further,

But my legs are bruised and scratched.

The bony rocks appear chiseled,

The pines look as if they had been dyed.

Sitting down, I feel like a small bird,

As I look out at the crowd of peaks gathered before me.

Having ascended the heights to the brink of the abyss,

I hold fast and ponder the need to sincerely face criticism.

Wherever a road ends, I will set myself down,

Wherever a source opens, I will build a temple.

A

ll this suffices to nourish my eyes,

And rest my feet.

(Translation by Yangming Chu and Maxwell K. Hearn)

1. A traveler draws the viewer into the landscape.

2. Buddhist and Daoist temples were often located in the mountains away from urban settings and thus served as restful retreats from city life. In the years immediately following the Manchu conquest, they also provided sanctuary for Ming loyalists who wished to withhold their support of the Manchu Qing dynasty.

3. High in the mountains, another travelerÑperhaps a self-portrait of the artistÑsits in meditation beneath a natural stone arch. One such rock bridge, located on Mount Tiantai, a site sacred to Buddhists, was said to provide access to paradise for anyone able to cross it.

Wang Hui

(Chinese, 1632–1717)

To consolidate Manchu authority over China, the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662–1722) made a second tour of the south, in 1689, and later commissioned Wang Hui to record the momentous event. Breaking down the journey into episodes, the artist designed a series of twelve massive handscrolls; he painted most of the landscape himself but left the figures, architectural drawings, and more routine work to his assistants.

This scroll, the third in the set, shows the route of the emperor and his entourage from the city of Ji'nan to Mount Tai, in Shandong Province, a distance of about thirty miles that the party covered February 5–6, 1689. Throughout the scroll, which is more than forty-five feet long, soldiers, porters, and officials in the advance party wend their way on horseback and on foot through the countryside, up winding mountain paths, and through peaceful villages on their way to Mount Tai, the "cosmic peak of the East," where Kangxi was to conduct a heaven-worshipping ceremony.

More of the Scroll

Example #1 from the Scroll

Example #2 from the Scroll

Example #3 from the Scroll

Example #4 from the Scroll

Example #5 from the Scroll

Example #6 from the Scroll

Example #7 from the Scroll

Example #8 from the Scroll

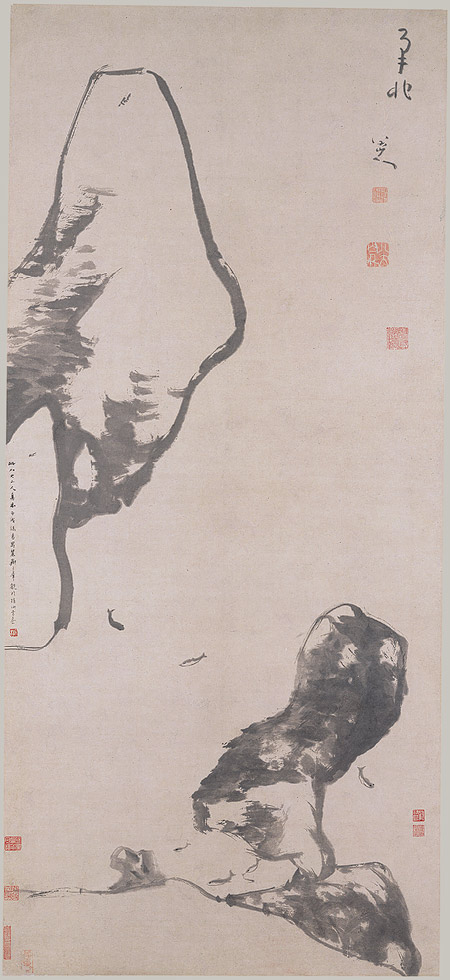

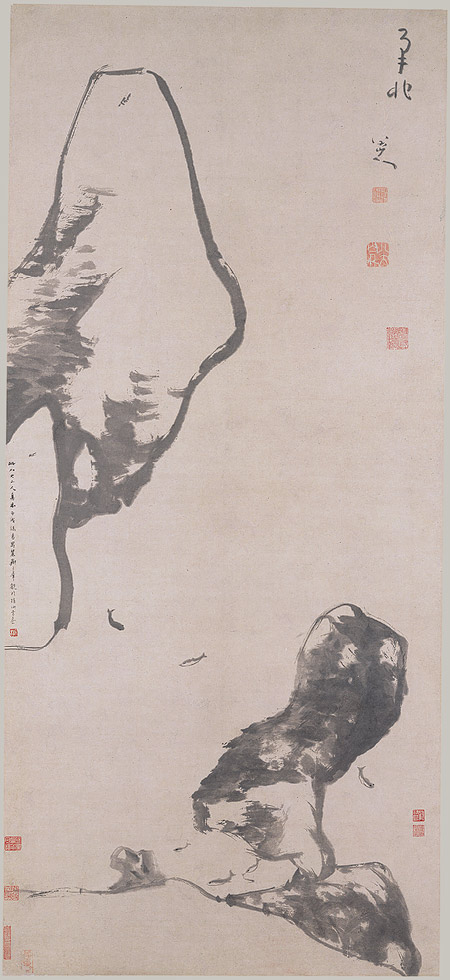

Bada Shanren (Zhu Da)

(Chinese, 1626–1705)

To disguise his identity, Zhu Da, a scion of the Ming imperial family, took refuge in a Buddhist temple after the Manchu conquest of 1644. About 1680, he renounced his status as a monk and began producing paintings and calligraphy in order to support himself. In 1684, he took the biehao (artistic name) Bada Shanren (Mountain Man of the Eight Greats). A staunch Ming loyalist throughout his life, Bada used painting as a means of protest. His is the poignant voice of the yimin, the "leftover subjects" of the fallen dynasty.

This painting is typical of the bold, enigmatic images that Bada produced during the last twenty years of his life. The seemingly innocuous subject, a garden pond framed by two ornamental rocks, becomes, in his rendition, profoundly unsettling. Were it not for seven tiny fish that swim beneath the two rock forms, transforming the blank paper into a body of water, the image would be unrecognizable. Six of the fish are shown in profile, but the seventh appears as if seen from above, leaving the viewer disoriented; the absence of a horizon line adds to the unsettling effect. Treating the image as a calligraphic design, Bada juxtaposes large and small, solid and void, and heavy and light, creating a tension between flat shapes and three-dimensional volumes that heightens the disturbing quality.

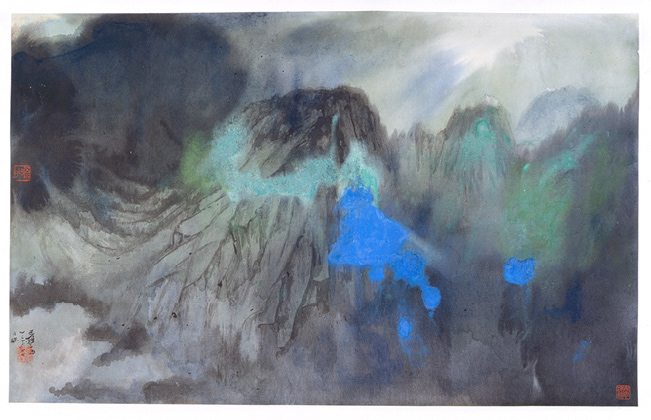

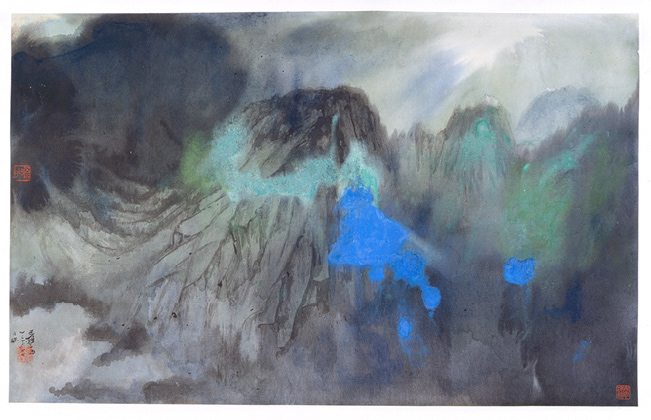

Zhang Daqian

(Chinese, 1899–1983)

After 1949, Zhang lived for a time in Hong Kong and India before building residences in São Paolo, Carmel (in California), and Taiwan. His long residency outside China inevitably brought him into contact with currents of modern Western art, including Abstract Expressionism. This work, painted with intense mineral colors and broad washes of layered ink, may represent Zhang's response to such influences.

Zhang maintained that such works, which first appeared in 1956, when he was in Europe, derived from the "broken-ink" techniques of random splashing and soaking used by Tang dynasty (618–907) artists, but it seems more likely that his encounter with Western abstract art encouraged him to carry further the Japanese technique of splashed colors that he had used in earlier works.

Clearly he welcomed the liberating effect of this painting mode on his creativity, which gave a spontaneity to his compositions. In spite of their abstract qualities, however, these paintings remained resolutely descriptive of the natural world. Here, Zhang first applied ink and color in a seemingly random manner, then added contour lines and other pictorial details in order to transform his composition into a highly suggestive vision of storm-engulfed mountains suddenly illuminated by a burst of sunlight that has turned the somber clouds iridescent.

|