| Emily Carr

The Art History Archive - Canadian Born December 13th 1871 – Died March 2nd 1945. Canadian Artist and Writer: Emily Carr studied in San Francisco in 1889-95, and in 1899 she travelled to England, where she was involved with the St. Ives group and with Hubert von Herkomer's private school. She lived in France in 1910 where the work of the Fauves influenced the colourism of her work and she came into contact with Frances Hodgkins. Discouraged by her lack of artistic success, she returned to Victoria where she came close to giving up art altogether. However, her contact with the Group of Seven in 1930 resurrected her interest in art, and throughout the 1930s she specialized in scenes from the lives and rituals of Native Americans. She also showed her awareness of Canadian native culture through a number of works representing the British Columbian rainforest. She lived among the native Americans to research her subjects. Many of her Expressionistic paintings represent totem poles and other artefacts of Indian culture. Emily Carr Chronology of Paintings

Detailed Biography She was born in Victoria, British Columbia, and moved to San Francisco in 1890 to study art after the death of her parents. In 1899 she travelled to England to deepen her studies, where she spent time at the Westminster School of Art in London and at various studio schools in Cornwall, Bushey, Hertfordshire, and elsewhere. In 1910, she spent a year studying art at the Académie Colarossi in Paris and elsewhere in France before moving back to British Columbia permanently the following year. Carr was most heavily influenced by the landscape and First Nations cultures of British Columbia, and Alaska. Having visited a mission school beside the Nuu-chah-nulth community of Ucluelet in 1898, in 1908 she was inspired by a visit to Skagway and began to paint the totem poles of the coastal Kwakwaka’wakw, Haida, Tsimshian, Tlingit and other communities, in an attempt to record and learn from as many as possible. In 1913 she was obliged by financial considerations to return permanently to Victoria after a few years in Vancouver, both of which towns were, at that time, conservative artistically. Influenced by styles such as postimpressionism and Fauvism, her work was alien to those around her and remained unknown to and unrecognized by the greater art world for many years. For more than a decade she worked as a potter, dog breeder and boarding house landlady, having given up on her artistic career. In the 1920s she came into contact with members of the Group of Seven (artists) after being invited by the National Gallery of Canada to participate in an exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art, Native and Modern. She travelled to Ontario for this show in 1927 where she met members of the Group, including Lawren Harris, whose support was invaluable. She was invited to submit her works for inclusion in a Group of Seven exhibition, the beginning of her long and valuable association with the Group. They named her 'The Mother of Modern Arts' around five years later. The Nuu-chah-nulth of Vancouver Island's west coast had nicknamed Carr Klee Wyck, "the laughing one." She gave this name to a book about her experiences with the natives, published in 1941. The book won the Governor General's Award that year. Her other titles were The Book of Small (1942),The House of All Sorts (1944) and Growing Pains (1946) Pause and The Heart of a Peacock (1953), and in 1966, Hundreds and Thousands. They reveal her to be an accomplished writer. Though mostly autobiographical, they have been found to be unreliable as to facts and figures if not in terms of mood and intent. Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, Emily Carr Elementary School in Vancouver, British Columbia, Emily Carr Middle School in Ottawa, Ontario and Emily Carr Public School in London, Ontario are named after her. Emily Carr is interred in the Ross Bay Cemetery in Victoria.

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

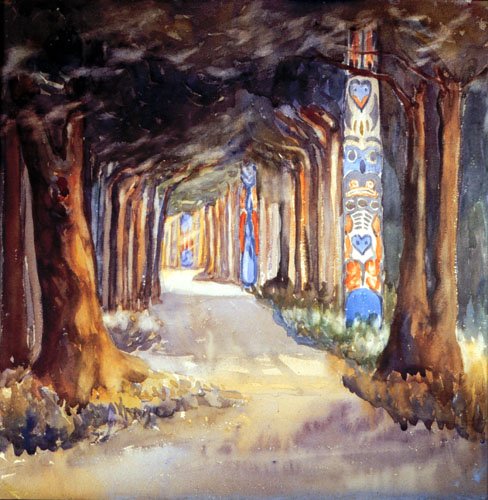

Emily Carr's Trees Emily Carr experienced an ecstatic identification with the spirit of nature, particularly as she found it in British Columbia. There the cool, gray climate, the proximity of water and most particularly the presence of trees offered her endless opportunity for artistic reflection and growth. To speak of Emily Carr's trees is to seize on the central subject of her work, both as metaphor and form. Like a great axis mundi, the tree centers and grounds most of her paintings. And as a mythico-ritual subject in Carr's work, the tree corresponds in importance to the centerpost often present in her paintings of the homes of native peoples in the Pacific Northwest. In 1935 Carr spoke before a literary society in Victoria about her art, a talk later published as "The Something Plus in a Work of Art." That "something," Carr explained, was what characterized great works of art - a kind of spiritual connection between the artist and an ideal. It was a connection that echoed Plato as well as the transcendentalists, whom she quoted. But it was more. Carr also brought the Japanese concept of Sei Do into her definition: "the transfusion into the work of the felt nature of the thing to be painted." Like Georgia O'Keeffe, Carr was receptive to principles and practices of Asian art. Carr's influences were received via other artists, particularly Mark Tobey, whose advice and teaching she had sought a few years earlier. The felt nature of the thing - its essence, its distinguishing core. For a painter whose chief subject was trees, Sei Do was treeness, and the expression of it her life's work. Carr had begun to discover its power very early in her career, when she animated trees in a 1905 political cartoon for a Victoria weekly periodical. Captioned "The Inartistic Alderman and the Realistic Nightmare," the cartoon was accompanied by the following poem: "Ye ghosts of all the dear old trees, The oak, the elm, the ash, Nightly those gentlemen go tease, Who hew you down like trash." Carr, it seems, had already seen the dangers posed by unrestrained tree cutting, a cause she would champion all her life. Trees, she suggests, possess a life of their own and should not be wantonly felled. It was an idea that was rarely popular in British Columbia, where the logging industry yearly consumed ever more of the virgin forests. Cartooning could not hold Carr's interest for long; she was after something more deeply expressive in the forest. In 1934 she chastised herself for flagging in her work: "I am hedging, not facing the problem before me how to express the forest - pretending I must do this and that first ... but the other should come first; it's my job." By that time Carr had spent years investigating the forest, absorbing all she could of tree existence. Her journals are full of her communion with trees, her admiration of them, and, ultimately, her close identification with them. Because Carr wrote so much about her life and her artistic struggle - unlike O'Keeffe - we can more readily see how she projected her feelings onto trees. Typical are her remarks "Trees are so much more sensible than people, steadier and more enduring" and "I ought to stick to nature because I love trees better than people." The latter statement echoes that of O'Keeffe to her friend Hartley. In their paintings of trees both Carr and O'Keeffe made transcriptions from visual experience, and each artist searched out rhythmic patterning and movement within arboreal structure, although there is no evidence that either painter knew the other's work before 1930. Both often cropped trees, and both made much of the negative spaces between branches. Carr's work in the 1920S usually stayed closer to gritty, palpable realism, while O'Keeffe's toyed with space and pressed toward decorative abstraction. The differences are significant. In 1930 Carr's and O'Keeffe's interest in trees intersected. That spring Carr visited New York, where, in the company of Arthur Lismer, an acquaintance who was a member of the Group of Seven, she sought out new painting. At An American Place a number of O'Keeffe's paintings were still on exhibit from her annual show. Most were based on her previous summer's visit to Taos, including The Lawrence Tree. Carr and O'Keeffe apparently discussed the painting at some length, during which O'Keeffe related the work's connection both to her experience at the Lawrence cabin and to Lawrence's passage about the great pine in St Mawr. Apparently these ideas lingered in Carr's mind, for later that year she copied Lawrence's description into her journal, though with a qualifying comment: "It's clever, but it's not my sentiments nor my idea of pines, not our north ones anyhow. I wish I could express what I feel about ours, but so far it's only a feel and I have not put it into words."

|

A List of Women Artists

Women Photographers

A List of Canadian Artists

|

||||||||||||||||

She continued, adding her intent to try to find words for the great pines, because "trying to find equivalents for things in words helps me find equivalents in painting. It is an interesting inversion of Lawrence's great skill, translating from the language of the eye to that of the ear. The search for equivalents also touches on O'Keeffe, who with Stieglitz thought deeply about the issue; unlike Lawrence or Carr, however, O'Keeffe found them most often in photography or music, not words.

She continued, adding her intent to try to find words for the great pines, because "trying to find equivalents for things in words helps me find equivalents in painting. It is an interesting inversion of Lawrence's great skill, translating from the language of the eye to that of the ear. The search for equivalents also touches on O'Keeffe, who with Stieglitz thought deeply about the issue; unlike Lawrence or Carr, however, O'Keeffe found them most often in photography or music, not words.

To find a visual vocabulary for what she felt about Canadian trees, Carr launched into a series of large studio drawings in charcoal on paper, based on trees but exploring form in a conceptual manner. Though Carr had long practiced drawing as a record of what she saw and thought, this 1930-31 series constitutes what Doris Shadbolt has called "the refined product of a period of study, which she seems not to have repeated at any other time in her life." That this extraordinarily free body of work followed directly upon Carr's visit to New York invites speculation that it was undertaken in response to her conversation with O'Keeffe, who had also used drawings particularly large, expressive studio charcoals during her own breakthrough period in 1915. Had O'Keeffe recommended such liberating exercises? Carr's journal entries indicate a readiness for new ideas: in January 1931 she is weary of past directions, writing, "My old things seem dead. I want fresh contacts, more vital searching." Her words are curiously reminiscent of O'Keeffe's two years earlier when, about to make a fresh beginning in the Southwest, the artist complained of her recent work, "It was mostly all dead for me." Carr seldom stretched for abstraction as much as O'Keeffe, but the 1930-31 charcoals seem to have furthered her movement away from preoccupation with native imagery and toward a search for nature's formal equivalents. At least one of these drawings may be directly responsive to Lawrence and O'Keeffe. Untitled [Formalized Cedar] and two closely related oils, Red Cedar (1931; Vancouver Art Gallery) and Tree Trunk, are particularly striking as answering motifs. With their central, upward thrusting trunks, these paintings suggest that O'Keeffe's The Lawrence Tree and her jack in the pulpit series, which Carr had also seen during the New York trip, had shown Carr the power of a symbol embedded in a reductivist image. Carr's responses, particularly her Tree Trunk and the formalized cedar drawing, demonstrate a new simplicity in her work, as well as the strong possibility of sublimated eros - a suggestion that would have horrified the prim Emily, simultaneously repelled by and drawn to Lawrence's nature based sexuality. Perhaps it was Lawrence's characterization of the pine as a "passionless, non-phallic column, rising in the shadows of the pre-sexual world" that made Carr feel she was on safe ground. In any case, she was fascinated (like O'Keeffe) by Lawrence's attention to the darker side of nature, a symbolism of death as well as life. If O'Keeffe had acknowledged that shadowy zone in Dead Tree, Bear Lake, Carr painted it in Old Tree at Dusk. The tree's spiraling trunk and downward drooping branches are strongly reminiscent of O'Keeffe's dead tree, a painting Carr might also have seen during her New York visit. What Carr definitely saw in New York was an exhibit of Arthur Dove's work at An American Place. On display were twenty-seven recent paintings by the romantically inclined Dove, whose explorations of abstractions derived from nature parallel those of O'Keeffe. A work such as Dove's charcoal Thunderstorm uses angular geometries to suggest the crackling energy of lightning. O'Keeffe had used similar zig zag or sawtooth shapes in works from the Line period. Early in the 1930s, whether in response to the increasing abstraction in Lawren Harris's work (as suggested by Carr scholars) or as I would argue with Dove's or O'Keeffe's angularities in mind, Carr introduced stronger geometric forms into her painting. Grey, discussed above, and an untitled black and gray forest interior from 1931-32 show Carr moving into the most abstract phase of her forest paintings. Zig-zagging shafts of light, a reductivist palette, and strong geometric patterning reveal Carr's interest in cubist derived form. Equally abstract, but far less angular, is Carr's sweeping Abstract Tree Forms. Great ribbons of color undulate across the surface of the painting; the red in the foreground encloses a deep tunnel form, like the sinuous wrapped shapes in O'Keeffe's paintings of music. Inside this space, however, is a dark bulbous form perhaps a tree stump, a fragment of a downed totem pole, or even the form of the artist herself. The freedom of the work owes as much to materials - thinned oil on paper - as to formal conception. It began as a practical effort: Carr needed to cut her expenses for materials, and she wanted to be able to work large and rapidly. She bought big sheets of inexpensive manila paper, which yielded paintings of consistent size that were simpler to frame and exhibit. To transport the paper and paintings, she made a folding drawingboard. And for paint she chose good quality white housepaint thinned with gasoline, which could be supplemented with oils, if necessary, on her return to the studio. Most days Carr could produce three of these paintings, which she tacked on the walls of her caravan or cabin overnight. A friend who often painted with her remembered that Carr liked to study her previous day's work in the bright morning light. Working large, she thinned the oil to admit light and air into the composition. Its quick drying capabilities gave her some of the fluidity of watercolor yet provided more opacity and solidity. Not least, the materials were so cheap that she could afford to be profligate in her experiments. Carr made many of these oil on paper works between 1933 and 1936. About them she wrote: "I've learned heaps in the paper oils - freedom and direction. You are so unafraid to slash away because material scarcely counts. You use just can paint and there's no loss with failures. I try to do one almost every day." Carr sometimes relied on dreaming to press her tree paintings into greater simplification and abstraction. As she wrote, "Last night I dreamed that I came face to face with a picture I had done and forgotten, a forest done in simple movement, just forms of trees moving in space. That is the third time I have seen pictures in my dreams, a glint of what I am striving to attain." O'Keeffe had also developed the capacity to incorporate dreaming into her landscapes, a practice that seems to have facilitated her own impulse to abstraction. In a letter to Dorothy Brett she referred to "that memory or dream thing I do that for me comes nearer reality than my objective kind of work." One thinks here of Gauguin's admonition to the artist to "dream before nature." For both Carr and O'Keeffe, letting go of direct, detailed observation was a key to finding other truths in the landscape. Carr returned in the 1930s to tree subjects she had painted early in her career, and we can see in the comparison how far her conception of Sei Do had evolved. Her early sedate rows of trees give way to later ones, like Sombreness Sunlit, in which light, and perhaps wind, take visible form and become the real subjects of the painting. All is movement, all light, perhaps accompanied by sound. Carr wrote about these sensory overlaps, a concept known to modernists as synesthesia: "If the air is jam full of sounds which we can tune in with, why should it not also be full of feels and smells and things seen through the spirit, drawing particles from us to them and them to us like magnets?" Such sensory transfers had been made especially visible to Carr during her 1930 New York visit, when she saw the work of Kandinsky and Charles Burchfield; the latter artist was having an exhibit of his early watercolors at the Museum of Modern Art at the time. His brooding works like Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night exaggerate the expressionistic qualities in plants, buildings, and natural surroundings to make them seem alive with menace. As Ruth Appelhof points out, after seeing Burchfield's work Carr began "to employ rhythmic lines to denote atmospheric movement and as a formal means of unifying the compositions." Trees figure importantly in the moody spatial evocations of both artists. A work like Carr's oil on paper sketch Chill Day in June employs those devices to great expressionist effect. By now the medium we saw introduced in Abstract Tree Forms about six years earlier had taken Carr's work in decidedly new directions. Although Carr herself referred to her more than two hundred of these oils on paper as "sketches," the term is somewhat misleading; they are finished works in their own right. It is true that she borrowed elements from them for later canvases; but what Carr discovered through the new medium was itself pivotal: in oil on paper she learned to join her means and ideas seamlessly. Great sweeps and washes of color, punctuated with seemingly careless dashes, flicks, and strokes, explore surface and depth simultaneously. Filled with light and air, these works break down the impenetrable wall of green seen in her early forest canvases. Moving beyond the Group of Seven, who had taught her something about vastness, she now opened up space even more in beach scenes like Strait of Juan de Fuca. And in an oil on paper work called Forest, color, air, and light chase one another with abandon. In paintings such as this one, Carr's exuberant paint application best expresses her belief in the unquenchable vitality of trees. Of the breadth and spontaneity her oil on paper technique afforded her, Carr concluded, "I feel I have gained a lot by its use. It is inexpensive, light to carry and allows great freedom of thought and action." Criticized by some for their large size, she justified the scale by saying, "Woods and skies out west are big you can't squeeze them down." Carr's trees developed in many moods and moments. She never seemed to exhaust their expressive possibilities, probably because she identified so closely with them. Trees were the botanical counterpart of her own imagined existence in nature: varied, changing, joyous, despondent. In the latter mood, feeling alienated from people, she wrote of herself as "exposed to all the ill winds like a lone old tree with no others round to strengthen it against the buffets with no waving branches to help keep time." When the persistent efforts of loggers decimated the old-growth forests in certain areas, Carr returned to the idea she had first used in her 1905 cartoon: she anthropomorphized trees. Loggers were "executioners," she now declared; the stumps mute mourners or tombstones. These things she described, both in paint and in words: "There's a torn and splintered ridge across the stumps I call the 'screamers.' These are the unsawn last bits, the cry of the tree's heart, wrenching and tearing apart just before she gives that sway and the dreadful groan of failing, that dreadful pause while her executioners step back with the saws and axes resting and watch." Significantly, the trees have a sex - female, in Carr's thinking; their pain is hers. Her paintings of stumps often continue the theme of scarred flesh; they read like amputations. Loggers Culls (1935; Vancouver Art Gallery), Stumps and Sky (c. 1934; Vancouver Art Gallery), and Swaying are three examples of such imagery. In the latter painting surviving trees stand like sentinels in a graveyard of stumps. On the other hand, when Carr entitles a painting Laughing Forest or Happiness (both c. 1939; private collections), we can be sure that she is projecting her own positive emotions onto the forest. The trees seem, at times, to be singing, a concept known to O'Keeffe as well. Georgia O'Keeffe wrote In 1915 of "the woods turning bright ... and the pines singing," but the words could as easily have been Carr's." In their seasonal and annual cycles, trees offered Carr the constant prospect of renewal. She tapped their energy for her own work. Musing on reawakening her strength at age sixty-nine, she wrote: "I think I shall start new growth, not the furious forcing of young growth but a more leisurely expansion, fed from maturity, like topmost boughs reflecting the blue of the sky." A painting such as Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky expresses that vision of high waving foliage, reaching upward for release and renewal in nature. Often release took the form of spiritual redemption for Carr, whose religious wanderings brought her eventualy to a highly personal form of Christianity. The forest as religious refuge is expressed in such paintings as Cedar Sanctuary and Wood Interior (c. 1929-30; private collection), which frame space as if it were within sacred precincts. The interiority there is the visual correlative of her own internal questioning: "Why do you go back and back to the woods unsatisfied, longing to express something that is there and not able to find it? This I know, I shall not find it until it comes out of my inner self, until the God quality in me is in tune with the God in it." Carr's trees form the axis around which her work rotates. Whether she studied them as native totem poles, as foliage curtains in living walls of jungle, as whirling, spiraling young evergreens against the sky, as murdered stumps, or as pillars within her intimate forest sanctuaries, Carr's trees form the thematic and formal scaffolding upon which her whole oeuvre was constructed. - From "Carr, O'Keeffe, Kahlo: Places of Their Own"

| |||||||||||||||||