| Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) The Art History Archive - Abstract Art German Abstract Art Movement

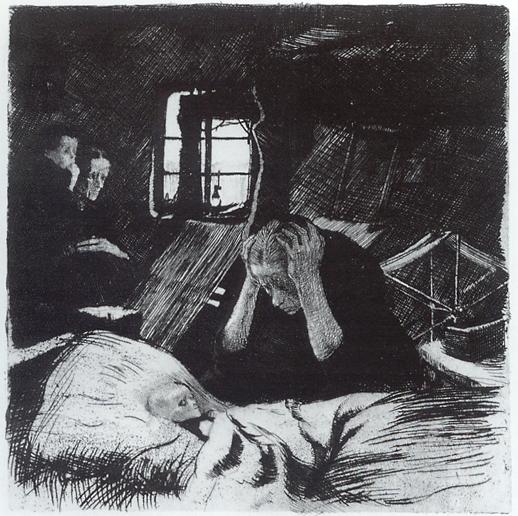

Right: Kathe Kollwitz - Woman with Dead Child, 1903 Die Neue Sachlichkeit (The New Objectivity) was a pseudo-Expressionist movement founded in Germany in the aftermath of World War I by Otto Dix and George Grosz. It is characterized by a realistic style combined with a cynical, socially critical philosophical stance. Many of the artists were anti-war. Two major trends were identified under Neue Sachlichkeit. The so-called Verists, including Otto Dix and George Grosz, aggressively attacked and satirized the evils of society and those in power and demonstrated in harsh terms the devastating effects of World War I and the economic climate upon individuals. Max Beckmann was connected with these artists. A second term, Magic Realists, has been applied to diverse artists, including Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Alexander Kanoldt, Christian Schad, and Georg Schrimpf, whose works were said to counteract in a positive fashion the aggression and subjectivity of German Expressionist art. Other artists associated with the movement included Max Beckmann and Christian Schad. Die Neue Sachlichkeit/The New Objectivity as a movement is still questioned by some art historians, just as the literary counterpart is questioned by some literary scholars. Its characteristics are as follows:

Comparison with Expressionism:

Kathe Kollwitz (1867-1945) Unlike Modersohn-Becker's robust and monumental depictions of motherhood, Kathe Kollwitz's imagery is marked by poverty stricken, sickly women who are barely able to care for or nourish their children. Kollwitz's art resounds with compassion as she makes appeals on behalf of the working poor, the suffering and the sick. Her work serves as an indictment of the social conditions in Germany during the late 19th and early 20th century. The daughter of a well to do mason, Kathe Schmidt was born in East Prussia. Her father encouraged her to draw and when she was 14 years old she began art lessons. She attended The Berlin School of Art in 1884 and later went to study in Munich. After her marriage to Dr. Karl Kollwitz in 1891, the couple settled in Berlin living in one of the poorest sections of the city. It was here that Kollwitz developed her strong social conscious which is so fiercely reflected in her work. Her art features dark, oppressive subject matter depicting the revolts and uprisings of contemporary relevance. Images of death, war and injustice dominate her work. Kollwitz was influenced by Max Klinger and the realist writings of Zola and she worked with a variety of media including sculpture, and lithography.It may be argued that her work was an expression of her tumultuous life. She came into contact with some of the cities most needy people and was exposed to great suffering due to the nature of her husband's work. Her personal life was marred by hardship and heartache. She lost her son to World War I and her grandson to World War II and these losses contributed to her political sympathies. Kathe Kollwitz became the first woman elected to the Prussian Academy but because of her beliefs, and her art, she was expelled from the academy in 1933. Harassed by the Nazi regime, Kollwitz's home was bombed in 1943. She was forbidden to exhibit, and her art was classified as "degenerate." Despite these events, Kollwitz remained in Berlin unlike artists such as Max Beckman and George Grosz who fled the country. She later died in 1945. Right: George Grosz - Metropolis, 1917 Works by Kathe Kollwitz:

OTHER ARTISTS

"You know, if one paints someone's portrait, one should not know him if possible. No knowledge! I do not want to know him at all, I only want to see what is there, on the outside. The inner follows by itself. It is mirrored in the visible." - Otto Dix

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||