| The Origins of Surrealism

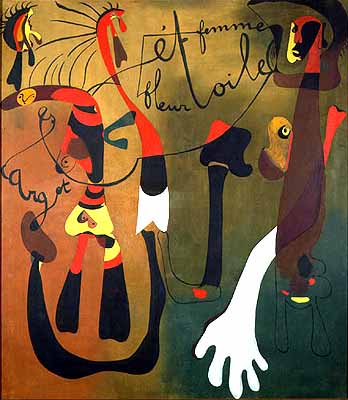

Historical Origins of The Surrealist Art Movement Last Updated: August 2011. By Charles Moffat. Edited by Suzanne MacNevin. See also "The Major Works of DADA & Surrealism, including Influences". Sometimes through history, something comes along that changes everything as it has been known thus far. In the 1920’s, such an art movement came around that changed the way art was defined. The Surrealist art movement combined elements of its predecessors, Dada and cubism, to create something unknown to the art world. The movement was first rejected, but its eccentric ideas and unique techniques paved the way for a new form of art. The Surrealist art movement stemmed from the earlier Dada movement. Dada was a movement in which artists stated their disgust with the war and with life in general. These artists showed that European culture had lost meaning to them by creating pieces of “anti-art” or “nonart.” The idea was to go against traditional art and all for which it stood. “Dada” became the movement’s name as a baby-talk term to show their feeling of nonsense toward the art world (de la Croix 705). Art from this movement was often violent and had an attitude of combat or protest. One historian stated that, “Dada was born from what is hated” (de la Croix 706). Though the movement was started to emphasize nonconformity, Picabia declared Dada to be dead in 1922, saying that it had become too organized a movement (Leslie 58). Despite the fact that it was declared dead, the Dada movement planted the seeds of another, more organized movement. The Surrealist movement started in Europe in the 1920’s, after World War I with its nucleus in Paris. Its roots were found in Dada, but it was less violent and more artistically based. Surrealism was first the work of poets and writers (Diehl 131). The French poet, André Breton, is known as the “Pope of Surrealism.” Breton wrote the Surrealist Manifesto to describe how he wanted to combine the conscious and subconscious into a new “absolute reality” (de la Croix 708). He first used the word surrealism to describe work found to be a “fusion of elements of fantasy with elements of the modern world to form a kind of superior reality.” He also described it as “spontaneous writing” (Surrealism 4166-67). The first exhibition of surrealist painting was held in 1925, but its ideas were rejected in Europe (Diehl 131). Breton set up an International Exhibition of Surrealism in New York, which then took the place of Paris as the center of the Surrealist movement (Pierre i). Soon surrealist ideas were given new life and became an influence over young artists in the United Sates and Mexico. The ideas of Surrealism were bold and new to the art world. Surrealism is defined as “Psychic automatism in its pure state by which we propose to express- verbally, in writing, or in any other manner- the real process of thought. The dictation of thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason and outside any aesthetic or moral concerns” (Leslie 59). In other words, the general idea of Surrealism is nonconformity. This nonconformity was not as extreme as that of Dada since surrealism was still considered to be art. Breton said that “pure psychic automatism” was the most important principle of Surrealism. He believed that true surrealists had no real talent; they just spoke their thoughts as they happened (Leslie 61-63). Surrealism used techniques that had never been used in the art world before. Surrealists believed in the innocent eye, that art was created in the unconscious mind (Mak 1). Most Surrealists worked with psychology and fantastic visual techniques, basing their art on memories, feelings, and dreams (Scholastic 3). They often used hypnotism and drugs to venture into the dream world, where they looked for unconscious images that were not available in the conscious world. These images were seen as pure art (Mak 2). Such ventures into the unconscious mind lead Breton to believe that surrealists equaled scientists and could “lead the exploration into new areas and methods of investigation” (Leslie 61).

Surrealists strongly embraced the ideas of Sigmund Freud. His method of psychoanalytic interpretation could be used to bring forth and illuminate the unconscious (Surrealism 4167). Freud once said, “A dream that is not interpreted is like a letter that is not opened,” and Surrealists adapted this idea into their artwork (Sanchez 4). Although Surrealists strongly supported the ideas of Freud, Breton visited him in 1921 and left without his support (Leslie 61). Freud inspired many Surrealists, but two different interpretations of his ideas lead to two different types of Surrealists, Automatists and Veristic Surrealists. Automatists focused their work more on feeling and were less investigative. They believed automatism to be “the automatic way in which the images of the subconscious reach the conscious” (Sanchez 2). However they did not think the images had a meaning or should try to be interpreted. Automatists thought that abstract art was the only way to convey images of the subconscious, and that a lack of form was a way to rebel against traditional art. In this way they were much like Dadaists. On the other side Veristic Surrealists believed subconscious images did have meaning. They felt that these images were a metaphor that, if studied, could enable the world to be understood. Veristic Surrealists also believed that the language of the subconscious world was in the form of image. While their work may look similar, Automatists only see art where Veristic Surrealists see meaning (Sanchez 2-5). Surrealism drew elements from Cubism and Expressionism, and used some of the same techniques from the Dada movement (Leslie 4). Nonetheless there were certain techniques and devices that were characteristic to Surrealist art. Some devices including levitation, changing an object’s scale, transparency, and repetition are used to create a “typical” surrealist look (Scholastic 4). A very common Surrealist technique is the juxtaposition of objects that would typically not be together in a certain situation or together at all. This has been described as “beautiful as the encounter of an umbrella and a sewing-machine on a dissecting table” (de la Croix 710). Juxtaposition can be used to show a metaphor or to convey a certain message. Many surrealist artists painted very realistically but had one displaced object that changed the painting entirely. Another technique called “objective chance” used images found in nature that could not be created by an artist. Stencils and rubbings were used to utilize these images (Leslie 71). An additional characteristic of Surrealist art is the fact that many pieces have very obvious or simple titles stating the subject matter simply (de la Croix 709). These techniques are typical of most Surrealist art but it would not be correct to describe Surrealism as “typical.” Some of the most famous Surrealist artists used these techniques to make masterpieces. René Magritte, a Surrealist artist, used traditional techniques to paint very realistic images. As a poster and wallpaper designer, he learned to paint realistically. His art frequently depicted images of everyday life; however, he creatively changed some aspects to give his work certain meaning. Magritte was able to turn dull images into extraordinary ones. Magritte’s own image, dressed in a dark suit and bowler hat, frequently appeared in his work. Many of his paintings had sinister and violent meanings, and the importance of surroundings was often stressed (Scholastic 2-7). Although many Surrealist painters studied traditional art, Max Ernst was a self-taught painter. He felt that true subconscious art was the images in the minds of those thought to be insane. He studied philosophy and psychiatry and even visited an asylum to experience those images first hand (Leslie 69). His paintings repeatedly used the vegetable, the animal, the mineral, and the human kingdoms (Diehl 132). In 1925 he began to use frottage to express his feelings of fantasy and of the bizarre. Frottage is a rubbing technique in which the texture of an object is rubbed onto a piece of paper. These rubbings were then arranged into collages (Mak 1). Salvador Dali, one of the most famous Surrealist artists, was known for his wild art and a public personality to match. He once said, “It is not necessary of the public to know whether I am joking or whether I am serious, just as it is not necessary for me to know it myself” (Ballard viii). Dali first wrote poems, essays, and even books, his most famous being The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (Gregory 111). Inspired by the Dutch masters of the 17th century realism (de la Croix 710), Dali’s art was known for its realistic qualities. He used multiple symbolic images to suggest his subconscious. His paintings were odd, influenced by his dreams and his fear of sex (Mak 2). This fear was present in many of his works, which depict sexual and violent images. Dali felt that the three constants of life were “the sexual instinct, the sentiment of death, and the anguish of space and time” (Ballard i). He had two methods for creating art: the oniric-critical method and the paranoiac-critical method. In the former, the artist freezes and interprets his dreams through art. The latter is the science of painting so as to study the psyche through subconscious art (Sanchez 3-5). Dali rejected induced sleep used by other artists and termed his own style to be the paranoiac-critical method (Surrealism 4171). A few of his pieces even had the words “paranoiac critical” in their titles (Ballard). Even though he is one of the best know surrealist artists, in 1938 Dali dissociated himself from Surrealism and turned to Classicism. He stated his change as “a religious Renaissance based on a progressive Catholicism” (Gregory 107), and in 1940 he moved to the United States to take part in the commercial culture (Leslie 77). The Surrealist art movement opened the doors to a style of art that the world had never before seen. Odd techniques were used to paint and interpret images of the subconscious and the dream world. Though many Surrealist artists used traditional means of painting, they developed techniques to bring metaphor and meaning into their work. The obvious may have been stated but the meaning to Surrealist art was symbolic and often open to interpretation. This style and technique received much rejection by the art world but was eventually accepted and paved the way for other expressive forms of art.

Bibliography Ballard, J.G. Introduction. Dali. New York: Ballantine. 1974. de la Croix, Horst and Richard G. Tansey. Art Through the Ages. Atlanta: Harcourt, Brace, & World. 1970. Diehl, Gaston. The Moderns: A Treasury of Painting Throughout the World. New York: Crown. 1986. Gregory, Clive and Sue Lyon. Fantasy and Surrealism. New York: Marshall Cavendish. 1988. Leslie, Richard. Surrealism: The Dream of Revolution. New York: Smithmark. 1997. Mak, Alan. “Surrealism.” Abstract. 23 Sept. 2001. Pierre, José. Surrealist Painting. New York: Tudor. 1971. Sanchez, Monica. “Research on Surrealism in America.” Surrealism: The Art of Self Discovery. Abstract. 23 Sept. 2001. Scholastic Art. New York: Scholastic Inc., 1993. “Surrealism.” The New International Illustrated Encyclopedia of Art. 1970 ed.

|

|

|

| |